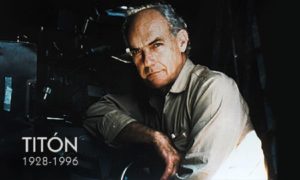

TOMÁS “TITÓN” GUTIÉRREZ ALEA, FILMMAKER.

Tomás “Titon” Gutiérrez Alea was born on December 11, 1928 he was a Cuban filmmaker. He wrote and directed more than 20 features, documentaries, and short films, which are known for his sharp insight into post-Revolutionary Cuba, and possess a delicate balance between dedication to the revolution and criticism of the social, economic, and political conditions of the country.

Born to a fairly well-off family, Alea was sent to college in Havana to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a lawyer. At about the same time he entered school, though, he acquired an 8mm camera and made two short films, El faquir (1947) and La caperucita roja (1947). Several years later he collaborated with fellow student (and future film great) Néstor Almendros on a short adaptation of a Franz Kafka story they named Una confusión cotidiana (1950). Upon graduation, Alea journeyed to Italy to study film directing for two years during the crest of neorealism at the famed Centro Sperimentale de Cinematografia.

EL MEGANO TRAILER.

He returned to Cuba in 1953 and joined the radical “Nuestro Tiempo” cultural society, becoming active in the film section, working as a publicist and aligning himself with Castro’s fight against the Batista regime. In 1955 Alea co-directed, with fellow society member ‘Julio Garcia Espinosa’, the 16mm short El mégano (1955), a semi-documentary about exploited workers, acted by nonprofessionals from the locales in which it was shot. The film was seized by Batista’s secret police because of its political content.

Soon after the Cuban revolution in 1959, Alea co-founded (with Santiago Álvarez) the national revolutionary film institute ICAIC (“Instituto del Arte y Industria Cinematografica”). He promptly made a documentary, Esta tierra nuestra (1959), full of hope for the new government’s plan to help the poor through agrarian reform, and has remained a pillar of the organization ever since. Alea’s diverse creative personality has led him to experiment with a broad range of styles and themes. His first feature, Historias de la revolución (1960), employs a neorealist style to present three dramatic sketches depicting the armed insurrection against Batista. Alea’s relatively straightforward approach to film style, however, would change, altered not only through his appropriation of Hollywood and art cinema stylistics but also by his increasingly personal attempts at self-expression.

GUANTANAMERA -Full Picture.

Alea returned yet again to the nexus between the sexual and the political with the best-known Cuban film of the 1990s, Strawberry and Chocolate (1993). The story of the unusual friendship that develops between a naive believer in Castro’s contemporary version of communism and a more experienced, gay critic of the regime was widely praised and just as widely attacked. Some found it atypically gentle for Alea and read its gay lead as a cover-up of Castro’s horrifying treatment of homosexuals, while others thought it needlessly provocative in its characterizations; such divergent responses only testify to the complexity typical of Alea’s tapestries. In 1994, “Strawberry and Chocolate” became the first Cuban film to receive an Oscar nomination as Best Foreign Film. Alea has written or co-scripted all his features and, in accordance with ICAIC’s collective approach to filmmaking, has served as advisor on two of the institute’s most stylistically innovative films: El otro Francisco (1975), directed by Sergio Giral, and One Way or Another (1978), directed by Sara Gomez.

The Hollywoodian black comedy La muerte de un burócrata (1966) cites not only Buñuel but also Mack Sennett and Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy as it criticizes, at an early point in the Castro regime, the administrative muck of the political system (Alea reused the gallows humor of the bureaucracy connected with burying a corpse for his road picture Guantanamera (1995), which began to appear at festivals in 1995 and 1996).

Hasta cierto punto (Up to a Certain Point) (ez’s wife, Mirta Ibarra.) The film underwent some censorship and remains to this day considered by Cuban critics one of his lesser works, though it is still highly regarded. The director himself said jokingly that the film was only successful “up to a certain point”.

Spouse: Mirtha Ibarra (m. ?–1996)

Children: Audry Gutierrez Alea, Natalia Gutiérrez

In the early 1990s, Gutiérrez fell into ill health, forcing him to co-direct his last two films with his friend Juan Carlos Tabío. The first, Fresa y Chocolate (Strawberry and Chocolate) (1993) became the first Cuban film to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. The film won the Silver Bear – Special Jury Prize at the 44th Berlin International Film Festival.

Titón, as he was known to his friends, died in Havana on April 16, 1996, at age 67. He is buried in the Colon Cemetery, Havana.

TOMÁS “Titón” GUTIÉRREZ ALEA, CINEASTA.

Tomás “Titón” Gutiérrez Alea nació el 11 de diciembre de 1928 y fue un distinguido cineasta cubano. Escribió y dirigió más de 20 largometrajes, documentales y cortometrajes, conocidos por su penetrante visión de la Cuba posrevolucionaria, y poseen un delicado equilibrio entre la dedicación a la revolución y la crítica de las condiciones sociales, económicas y políticas de el país.

Nacido en una familia bastante acomodada, Alea fue enviado a la universidad en La Habana para seguir los pasos de su padre y convertirse en abogado. Sin embargo, al mismo tiempo que ingresó a la escuela, adquirió una cámara de 8mm y realizó dos cortometrajes: El faquir (1947) y La caperucita roja (1947). Varios años más tarde colaboró con su colega Néstor Almendros (y el futuro gran cine) en una breve adaptación de una historia de Franz Kafka llamada Una confusión cotidiana (1950). Al graduarse, Alea viajó a Italia para estudiar dirección de cine durante dos años durante la cresta del neorrealismo en el famoso Centro Sperimentale de Cinematografía.

https://youtu.be/Iko66-zHADQ

FRESA Y CHOCOLATE TRAILER.

Regresó a Cuba en 1953 y se unió a la sociedad cultural radical “Nuestro Tiempo”, activándose en la sección de cine, trabajando como publicista y alineándose con la lucha de Castro contra el régimen de Batista. En 1955 Alea co-dirigió, junto a su compañero de la sociedad ‘Julio García Espinosa’, el cortometraje de 16 mm El mégano (1955), semi-documental sobre obreros explotados, actuado por no profesionales de las localidades donde fue fusilado. La película fue capturada por la policía secreta de Batista debido a su contenido político.

Poco después de la revolución cubana en 1959, Alea co-fundó (con Santiago Álvarez) el instituto nacional de cine revolucionario ICAIC (Instituto del Arte y Industria Cinematográfica). Con prontitud hizo un documental, Esta tierra nuestra (1959), lleno de esperanza para el nuevo plan del gobierno para ayudar a los pobres a través de la reforma agraria, y ha seguido siendo un pilar de la organización desde entonces. La diversa personalidad creativa de Alea le ha llevado a experimentar con una amplia gama de estilos y temas. Su primer largometraje, Historias de la revolución (1960), emplea un estilo neorrealista para presentar tres dramáticos esbozos que representan la insurrección armada contra Batista. Sin embargo, el acercamiento relativamente sencillo de Alea al estilo de la película cambiaría, alterado no sólo por su apropiación de Hollywood y la estilística del cine de arte, sino también por sus cada vez más personales intentos de autoexpresión.

Alea regresó nuevamente al nexo entre lo sexual y lo político con la película cubana más conocida de los años 90, Fresa y Chocolate (1993). La historia de la inusual amistad que se desarrolla entre un creyente ingenuo en la versión contemporánea de Castro del comunismo y un crítico gay más experimentado del régimen fue ampliamente elogiada y tan ampliamente atacada. Algunos lo encontraron atípicamente amable para Alea y leyeron aquella como un encubrimiento del tratamiento horrible de Castro hacia los homosexuales, mientras que otros lo consideraban innecesariamente provocador en sus caracterizaciones; Tales respuestas divergentes sólo atestiguan la complejidad típica de los tapices de Alea. En 1994, “Strawberry and Chocolate” se convirtió en la primera película cubana en recibir una nominación al Oscar como Mejor Película Extranjera. Alea ha escrito o co-guionado todas sus facciones y, de acuerdo con el enfoque colectivo del ICAIC, ha sido asesor de dos de las películas más innovadoras en el estilo del instituto: El otro Francisco (1975), dirigido por Sergio Giral y One Way O Otro (1978), dirigido por Sara Gómez.

La comedia negra de Hollywood La muerte de un burócrata (1966) cita no sólo a Buñuel, sino también a Mack Sennett y Stan Laurel y Oliver Hardy al criticar, en un momento temprano del régimen castrista, la suciedad administrativa del sistema político (Alea reutilizó la Humor de horca de la burocracia relacionada con enterrar un cadáver para su foto Guantanamera (1995), que comenzó a aparecer en festivales en 1995 y 1996).

La película sufrió cierta censura y sigue siendo hasta nuestros días considerada por los críticos cubanos una de sus obras menores, aunque sigue siendo muy apreciada. El propio director dijo en broma que la película sólo tuvo éxito “hasta cierto punto”, otra de sus producciones.

Cónyuge: Mirtha Ibarra (año -1996)

Hijos: Audry Gutierrez Alea, Natalia Gutiérrez

A principios de los años noventa, Gutiérrez cayó en mala salud, obligándolo a co-dirigir sus dos últimas películas con su amigo Juan Carlos Tabío. La primera, Fresa y Chocolate (1993), se convirtió en la primera película cubana nominada al Oscar de Mejor Película Extranjera. La película ganó el Oso de Plata – Premio Especial del Jurado en el 44 Festival Internacional de Cine de Berlín.

Titón, como era conocido por sus amigos, murió en La Habana el 16 de abril de 1996, a los 67 años. Esta enterrado en el Cementerio de Colón, La Habana.

Agencies/Wiki/IMDb / DanielYates / Internet Photos / YouTube / Arnoldo Varona/ thecubanhistory.com

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.