¿De dónde sacó tiempo este hombre para hacer lo que hizo?

Aunó las voluntades independentistas, fundó un partido político, organizó la guerra contra España. Después de los 17 años de edad, cuando salió deportado de Cuba tras cumplir prisión y trabajos forzados pese a su minoría de edad, vivió de manera casi permanente en el exilio. Cursó dos carreras universitarias en España; trabajó como abogado y tenedor de libros, fue maestro en Guatemala, Venezuela y Estados Unidos. Cónsul en Nueva York de varias repúblicas sudamericanas y su representante en conferencias internacionales. Orador. Periodista siempre. Creó y dirigió un periódico, Patria, y publicó varias revistas, entre ellas La edad de oro, para los niños de América, que escribía de cabo a rabo. Redactaba directamente en inglés para periódicos norteamericanos. Hizo teatro, escribió una novela. Como poeta, es de los más grandes del idioma, iniciador del modernismo, aunque a la postre no quepa en ninguna escuela… Sus obras completas –crónicas, artículos, ensayos, literatura, cartas, discursos…- suman casi treinta volúmenes de más de 300 páginas cada uno.

¿De dónde sacó tiempo este hombre que vivió solo 42 años para hacer lo que hizo? ¿Dejaron sus tareas políticas y profesionales tiempo para la vida privada? ¿Amó?

“Martí era un hombre necesitado de calor. Solo en las lides del amor o de la acción encontraba su propia temperatura”, dice Jorge Mañach en Martí el Apóstol, su insuperable biografía del Héroe Nacional de Cuba. Un hombre que a veces se enamoraba del amor más que de la mujer.

Tuvo un matrimonio contrariado del que le nació un hijo al que dedicó un poemario espléndido, Ismaelillo. Pero antes y después y a veces paralelamente dejó entrar a otras mujeres en sus fervores de desterrado.

Rosario de la Peña, La Musa, la George Sand de México, fue de las primeras. Y la actriz, también mexicana, Concha Padilla, con la que tuvo un idilio de “bruscas alternativas de beatitud y borrasca”. Ella fue la protagonista principal del drama Amor con amor se paga que el público mexicano pagó a Martí con largos aplausos.

Era muy celosa la Concha y tenía motivos para ello. Se mostraba cada vez más avara con el galán mientras él se prodigaba en atenciones con las demás mujeres. Galantuomo le llamaba un amigo, y él confesaba que quería dividirse “en cachitos” entre todas.

Doña Leonor, la madre, no veía con agrado los amoríos de Martí con Concha Padilla, “que podrá ser todo lo decente que se quiera, pero es una cómica”, y muchos de sus amigos tampoco. Manuel Mercado, su hermano mexicano, le metió por los ojos a la cubana Carmen Zayas Bazán, fina y elegante, que atraía, a su paso por la Alameda, las miradas de todos los jóvenes.

Luego de los amores turbulentos con la Concha, Carmen fue un remanso. Se comprometieron y Martí viajó a Guatemala. Allí conoció a María García Granados, hija de un ex Presidente de ese país. Fue una simpatía mutua, un acercamiento inmediato a aquella muchacha de 20 años de edad, rostro pálido y mirada suave. Él le descubrió el amor dormido y se le desbordaba la ternura cuando ella interpretaba al piano algún vals de Ardite.

Pídele ella que le escriba un poema en su álbum íntimo. Martí lo hace y la muchacha lo lee con pesar. Habla de amistad en sus versos, no de amor. Quiere él estrecharle la mano y ella se lleva el pañuelo a los ojos y huye al interior de la casa.

Nada había dicho Martí a sus amigos guatemaltecos de su compromiso con Carmen y el poema en el álbum de María, más que una mentira piadosa es para ella una cruel revelación.

Viaja él a México y regresa a Guatemala, casado. María muere. Años después Martí la inmortalizaría en La niña de Guatemala, uno de sus poemas más célebres y repetidos.

…Ella dio al desmemoriado / una almohadilla de olor. / El volvió, volvió casado. / Ella se murió de amor…

Con Carmen Zayas Bazán las cosas van a veces bien y casi siempre mal. Logra el deportado regresar a La Habana, donde nace su hijo, pero vuelven a desterrarlo y a partir de ahí la pareja se reunirá de cuando en cuando. Si se encuentran, media una paz diplomática entre ellos en un hogar difícil por la estrechez económica y los continuos reclamos que hacen a Martí sus ideales patrios. Un día, acogida a la protección del cónsul español en Nueva York, Carmen abandona a Martí para siempre. Es una mujer y acaso intuye que otro amor “sereno ya y doméstico le ha sustituido el amor esquivo”.

Porque a esa hora otra Carmen, Carmen Miyares, había aparecido ya en la vida del Apóstol. Y la llena. Está casada con el cubano Manuel Mantilla, enfermo de melancolía y parálisis. Es medio venezolana y medio santiaguera, robusta, parlanchina, simpática.

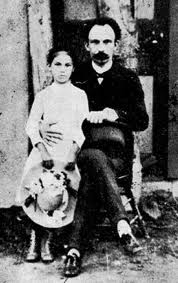

Mucho se ha hablado de esos amores. Algunos los niegan. A María, la hija de Carmen y en la que se repite el nombre de la niña de Guatemala, Martí la quiso con amor paternal. El parecido entre ambos es asombroso si se comparan sus retratos. ¿Era su padre? Poco importa precisarlo. A María Mantilla escribió Martí cartas desbordadas de cariño y consejos para la vida cuando él ya no estuviera.

La última de esas cartas, escrita semanas antes, la recibió María en Nueva York, el 19 de mayo de 1895, el mismo día que Martí, en Cuba, caía en combate frente a las tropas españolas. En ella le decía que llevaba su retrato sobre el corazón, como un escudo contra las balas.

OUR JOSE MARTI IN LOVE, IN HIS INTIMATE AND PRIVATE LIFE. PHOTOS.

Where did this man find the time to do what he did?

He united the independence movement, founded a political party, and organized the war against Spain. After the age of 17, when he was deported from Cuba after serving prison time and forced labor despite being a minor, he lived almost permanently in exile. He completed two university degrees in Spain; worked as a lawyer and bookkeeper; and was a teacher in Guatemala, Venezuela, and the United States. He was Consul in New York for several South American republics and their representative at international conferences. A speaker, he was always a journalist. He founded and edited a newspaper, Patria, and published several magazines, including La edad de oro, for the children of America, which he wrote from cover to cover. He wrote directly in English for North American newspapers. He performed plays and wrote a novel. As a poet, he is one of the greatest in the language, a pioneer of modernism, although ultimately he doesn’t fit into any school… His complete works—chronicles, articles, essays, literature, letters, speeches…—amount to almost thirty volumes of more than 300 pages each.

Where did this man, who lived only 42 years, find the time to do what he did? Did his political and professional duties leave time for his private life? Did he love?

“Martí was a man in need of warmth. Only in the struggles of love or action did he find his own temperature,” says Jorge Mañach in Martí the Apostle, his unsurpassed biography of Cuba’s National Hero. A man who sometimes fell in love with love more than with women.

He had a troubled marriage from which he had a son, to whom he dedicated a splendid collection of poems, Ismaelillo. But before and after, and sometimes in parallel, he allowed other women into his exile’s fervor.

Rosario de la Peña, The Muse, Mexico’s George Sand, was one of the first. And the actress, also Mexican, Concha Padilla, with whom he had a romance of “sudden alternations of bliss and storm.” She was the main protagonist of the play Amor con amor se paga (Love with Love is Paid), which the Mexican public paid tribute to Martí with prolonged applause.

Concha was very jealous, and she had good reason to be. She became increasingly stingy with her gallant while he lavished attention on other women. Galantuomo called him a friend, and he confessed that he wanted to divide him “into little pieces” among them all.

Doña Leonor, his mother, did not take kindly to Martí’s affairs with Concha Padilla, “who may be as decent as she wants, but she’s a comedian,” and neither did many of his friends. Manuel Mercado, his Mexican brother, had his eye on the fine and elegant Cuban Carmen Zayas Bazán, who, as she walked down the Alameda, attracted the attention of all the young men.

After his turbulent love affair with La Concha, Carmen was a haven. They became engaged, and Martí traveled to Guatemala. There he met María García Granados, daughter of a former president of that country. It was a mutual affection, an immediate rapport with that 20-year-old girl with a pale face and soft gaze. He revealed her dormant love, and tenderness overflowed when she played a waltz by Ardite on the piano.

She asked him to write a poem for her in her private album. Martí did so, and the girl read it with regret. He speaks of friendship in his verses, not of love. He wanted to shake her hand, and she put her handkerchief over her eyes and fled into the house.

Martí had said nothing to his Guatemalan friends about his engagement to Carmen, and the poem in María’s album, other than a white lie, is a cruel revelation to her.

He traveled to Mexico and returned to Guatemala, married. María died. Years later, Martí immortalized her in “The Girl from Guatemala,” one of his most famous and repeated poems.

…She gave the forgetful man / a scented pillow. / He returned, returned married. / She died of love…

With Carmen Zayas Bazán, things sometimes go well and almost always badly. The deportee manages to return to Havana, where his son is born, but he is exiled again, and from then on, the couple reunited from time to time. If they meet, a diplomatic peace is brokered between them in a difficult home due to financial hardship and the constant demands made on Martí by his patriotic ideals. One day, taken under the protection of the Spanish consul in New York, Carmen abandons Martí forever. She is a woman, and perhaps she senses that another love, “serene and domestic, has replaced the elusive love.”

Because by that time, another Carmen, Carmen Miyares, had already appeared in the Apostle’s life. And she filled it. She was married to the Cuban Manuel Mantilla, afflicted with melancholy and paralysis. She is half Venezuelan and half from Santiago de Compostela, robust, talkative, and charming.

Much has been said about these loves. Some deny them. Martí loved María, Carmen’s daughter, in whom the name of the girl from Guatemala is repeated, with paternal love. The resemblance between the two is striking when comparing their portraits. Was he her father? It hardly matters to specify. Martí wrote letters to María Mantilla, overflowing with affection and advice for life after his death.

The last of these letters, written weeks earlier, was received by María in New York, on May 19, 1895, the same day that Martí, in Cuba, fell in combat against Spanish troops. In it, he told her that he carried her portrait on his heart, like a shield against bullets.

Agencies/ Ciro Bianchi / Internet Photos/ www,TheCubanHistory.com/Arnoldo Varona.

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.

NUESTRO JOSE MARTI ENAMORADO, EN SU VIDA INTIMA Y PRIVADA. PHOTOS. * OUR JOSE MARTI IN LOVE, IN HIS INTIMATE AND PRIVATE LIFE. PHOTOS.

NUESTRO JOSE MARTI ENAMORADO, EN SU VIDA INTIMA Y PRIVADA. PHOTOS. * OUR JOSE MARTI IN LOVE, IN HIS INTIMATE AND PRIVATE LIFE. PHOTOS.