ERNEST HEMINGWAY EN CUBA: EL DIOS DE BRONCE DE LA LITERATURA AMERICANA Y “EL VIEJO Y EL MAR”. PHOTOS.

Corria el año 1951 en La Habana y “Bohemia”, la mas destacada y poderosa revista cubana de entonces había ofrecido a Ernest Hemingway entonces viviendo en la Capital cubana el publicar en una sola edicion la novela “El Viejo y el Mar”.

Miguel Ángel Quevedo, editor de la revista cubana quería publicar “El viejo y el mar”, como se había hecho con la revista Life antes de que la novela apareció en forma de libro. Quecedo le pidio al caricaturista David que contactara a Hemingway y le dijera que no podian pagar tanto como Life, pero que ellos tenian muchos deseos de presentar este trabajo en Cuba”. La revista de EE.UU. pagó Hemingway un dólar diez centavos de dólar por palabra, la novela tiene algo de 27 000 – que se completa con una suma de casi $ 30.000. Bohemia ofreció $5.000.

Hemingway aceptó la oferta, David recordó muchos años después. Pero puso dos condiciones. La traducción debia hacerla Lino Novas Calvo, el gran novelista de Pedro Blanco, El Negrero y La Noche de Ramón Yendía, un español que vivía en La Habana, murió en los EE.UU., y es una parte muy importante de la literatura cubana. Pidió además que la cantidad ofrecida será donado a beneficio de los pacientes del Leprosorio del Riincon en la Habana.

CINCO MILLONES EN DOS DÍAS

Y continua el destacado periodista Ciro Bianchi…”Quise recordar esta anécdota poco conocida y siempre mal contada ahora que El viejo y el mar cumplió 55 años de haberse publicado por primera vez. Cuando apareció, Hemingway no las tenía todas consigo. La crítica lo había vapuleado, y muy duro, tras la publicación de A través del río y entre los árboles (1950) una novela sentimental, se dijo, que relata el amor del viejo y gastado Cantwell por una muchacha, Renata. Era, en lo esencial, una historia autobiográfica; mientras recorría en el norte de Italia los escenarios de Adiós a las armas, el gastado Hemingway se había enamorado de la condesa Adriana Ivancich. Insistió en traerla a Finca Vigía, su casa habanera, y Mary, la cuarta esposa del narrador, que podía comprender el romance, pero no aquella convivencia, estalló en una crisis de celos homérica y continua..

Las críticas desfavorables a su libro lo hirieron hondo y ante ellas hizo lo que uno supone no haría un escritor de su estatura: se justificó, se defendió. Pero no abandonó su tarea. En el otoño de aquel mismo año de 1950 reanuda el trabajo en lo que llamaba The Sea Book y que nunca llegaría a publicar. De ahí se desprendió El viejo y el mar. Alguien lo convenció de que lo diera a conocer como una obra independiente. Hemingway se negó al comienzo, pero terminó haciéndolo.

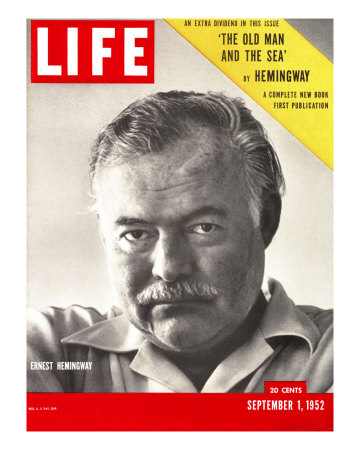

En abril de 1951, recordaba el periodista cubano Fernando G. Campoamor, tenía listo el borrador y lo remitió a Charles Scribner, su editor, en marzo del año siguiente. Su publicación en Life, el 1 de septiembre de 1952, fue una prueba. La revista vendió 5 325 447 ejemplares en 48 horas. El 8 de septiembre la casa Scribner puso a la venta la primera edición de la novela y ese mismo día dispuso la segunda edición. De inmediato, El viejo y el mar ganó la selección del Book of the Month Club, donde se le calificó como un libro “destinado a graduarse entre los clásicos de la literatura norteamericana”. Al año siguiente se alzó con el importante premio Pulitzer. Fue la antesala del Nobel que se le concedería a su autor, por el conjunto de su obra, en 1954.

Desde entonces se ha traducido a todos los idiomas y se llevó al sistema Braille para ciegos. Se adaptó al cine y a la TV. Más de cinco décadas después de su publicación inicial, El viejo y el mar sigue siendo un éxito en librerías y bibliotecas, aun cuando es ya uno y varios libros a la vez: incompleto, resumido, ilustrado, mal traducido, pirateado… A veces, en las ediciones en español, el nombre de Lino Novás Calvo se sustituye con un seco: “Traducción autorizada por el autor”.

EL DIOS DE BRONCE

Con la publicación de El viejo y el mar, Ernest Hemingway se ratificó como el dios de bronce de la literatura norteamericana. Todo un coro se alzó en su honor. William Faulkner dijo, sencillamente, que con esa novela su autor había encontrado a Dios. Campoamor, cubanísimo, tiró a choteo su verdad al afirmar: “Hemingway sabía de química y de geografía, de numismática y economía, de historia militar y de violines, e inventó el daiquirí especial al igual que inventó el monte Kilimanjaro, el idioma inglés y los casteros”.

Hemingway dijo: “Traté de hacer un viejo real, un muchacho real, un mar real, un pez real y tiburones reales. Pero si los hice bien y suficientemente verdaderos, pueden significar muchas cosas. Cuando se escribe bien y con sinceridad de una cosa, esa cosa significará después muchas otras cosas”. Añadiría que en su novela el mar es el mar, el viejo es el viejo y el pez es el pez… no hay en ella ningún simbolismo. No hay en sus páginas más que un viejo que pescaba solo en un bote en la Corriente del Golfo y hacía 84 días que no cogía un pez…

Puede suponerse que el autor leyó El viejo y el mar más de 200 veces. A esa conclusión se llega tras conocer la carta en la que dice: “Ahora las pruebas del libro están listas y no volveré a leerlo durante diez años. Porque cada vez que lo leo siento las mismas cosas que he sentido y 200 veces son suficientes”.

La anécdota de la novela es muy conocida. Su sentido es bien evidente. Hemingway lo pone en boca de Santiago, su protagonista: “El hombre no está hecho para la derrota. Un hombre puede ser destruido, pero no derrotado”.

El escenario de la novela es el mar y la lucha del viejo contra los tiburones, es la del hombre por la vida. Hay en ella alusiones a Cuba, como las hay, con mayor o menor extensión, en otros libros del escritor. En Verdes colinas de África recuerda a Cuba como una “isla larga, hermosa y desdichada”. Diría en alguna parte: “Amo este país y me siento como en casa; y donde un hombre se siente como en su casa, aparte del lugar donde nació, ese es el sitio al que estaba destinado”. Idea esa que reiteró cuando se supo ganador del Premio Nobel: “Este es un Premio que pertenece a Cuba, porque mi obra fue pensada y creada en Cuba, con mi gente de Cojímar, de donde soy ciudadano. A través de todas las traducciones está presente esta patria adoptiva donde tengo mis libros y mi casa”.

Tras la publicación de El viejo y el mar, Hemingway estaba en deuda con los pescadores de Cojímar, la pequeña localidad marina del este de La Habana. Cuando la cervecería Modelo, de El Cotorro, le rindió homenaje por el Nobel, aquellos hombres fueron los invitados de honor de la fiesta. Tras la publicación de la novela estaba en definitiva en deuda con la Isla, y eso explica quizás su decisión de ofrendar la medalla del Premio a la Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre, Patrona de Cuba.

ERNEST HEMINGWAY IN CUBA: THE BRONZE GOD OF AMERICAN LITERATURE. AND “THE OLD MAN AND THE SEA”. PHOTOS.

It was 1951 in Havana, and “Bohemia,” the most prominent and powerful Cuban magazine of the time, had offered Ernest Hemingway, then living in the Cuban capital, the opportunity to publish the novel “The Old Man and the Sea” in a single edition.

Miguel Ángel Quevedo, editor of the Cuban magazine, wanted to publish “The Old Man and the Sea,” as had been done with Life magazine before the novel appeared in book form. Quecedo asked the cartoonist David to contact Hemingway and tell him they couldn’t pay as much as Life, but that they were eager to present this work in Cuba. The US magazine paid Hemingway one dollar ten cents per word; the novel is about 27,000 words long—a sum totaling almost $30,000. Bohemia offered $5,000.

Hemingway accepted the offer, David recalled many years later. But he set two conditions. The translation was to be done by Lino Novas Calvo, the great novelist of Pedro Blanco, El Negrero, and La Noche de Ramón Yendía. A Spaniard who lived in Havana, died in the US, and is a very important part of Cuban literature. He also requested that the amount offered be donated to benefit the patients of the Riincon Leper Colony in Havana.

FIVE MILLION IN TWO DAYS

And the prominent journalist Ciro continues. Bianchi…”I wanted to recall this little-known and often misreported anecdote now that The Old Man and the Sea has been published for 55 years. When it appeared, Hemingway wasn’t entirely sure what he was doing. Critics had slammed him, and slammed him, after the publication of Across the River and Into the Trees (1950), a sentimental novel, it was said, that recounts the love of the aging, threadbare Cantwell for a young woman, Renata. It was, in essence, an autobiographical story; while touring northern Italy, the scenes of A Farewell to Arms, the threadbare Hemingway had fallen in love with Countess Adriana Ivanovich. He insisted on bringing her to Finca Vigía, his Havana home, and Mary, the narrator’s fourth wife, who could understand the romance but not the cohabitation, erupted in a Homeric and ongoing jealousy crisis.

The unfavorable reviews of his book hurt him deeply, and in the face of them, he did what one assumes a writer of his stature wouldn’t do: he justified himself, defended himself. But he didn’t abandon his task. In the fall of that same year, 1950, he resumed work on what he called The Sea Book, which he would never publish. From this, The Old Man and the Sea emerged. Someone convinced him to publish it as an independent work. Hemingway initially refused, but eventually did.

By April 1951, Cuban journalist Fernando G. Campoamor recalled, he had the draft ready and sent it to Charles Scribner, his editor, in March of the following year. Its publication in Life, on September 1, 1952, was a test. The magazine sold 5,325,447 copies in 48 hours. On September 8, Scribner’s published the first edition of the novel, and the second edition was released that same day. The Old Man and the Sea immediately won the Book of the Month Club selection, where it was described as a book “destined to graduate among the classics of American literature.” The following year, it won the prestigious Pulitzer Prize. This was the precursor to the Nobel Prize, which would be awarded to its author for his entire body of work in 1954.

Since then, it has been translated into every language and Braille for the blind. It has been adapted for film and television. More than five decades after its initial publication, The Old Man and the Sea remains a success in bookstores and libraries, even though it is now both a single book and several books at once: incomplete, abridged, illustrated, poorly translated, pirated… Sometimes, in Spanish editions, Lino Novás Calvo’s name is replaced with a brief: “Translation authorized by the author.”

THE BRONZE GOD

With the publication of The Old Man and the Sea, Ernest Hemingway established himself as the bronze god of American literature. A whole chorus rose up in his honor. William Faulkner said, simply, that with that novel, its author had found God. Campoamor, a true Cuban, mocked his truth when he declared: “Hemingway knew chemistry and geography, numismatics and economics, military history and violins, and he invented the special daiquiri just as he invented Mount Kilimanjaro, the English language, and the casteros.”

Hemingway said: “I tried to make a real old man, a real boy, a real sea, a real fish, and real sharks. But if I made them well and true enough, they can mean many things. When you write well and truthfully about one thing, that thing will later mean many other things.” I would add that in his novel, the sea is the sea, the old man is the old man, and the fish is the fish… there is no symbolism in it. There is nothing in its pages but an old man fishing alone in a boat in the Gulf Stream, who hadn’t caught a fish in 84 days…

It can be assumed that the author read The Old Man and the Sea more than 200 times. This conclusion is reached after reading the letter in which he says: “Now the proofs of the book are ready, and I won’t read it again for ten years. Because every time I read it, I feel the same things I’ve felt before, and 200 times is enough.”

The anecdote from the novel is well-known. Its meaning is quite evident. Hemingway puts it in the mouth of Santiago, his protagonist: “Man is not made for defeat. A man can be destroyed, but not defeated.”

The setting of the novel is the sea, and the old man’s fight against the sharks is man’s fight for life. There are allusions to Cuba in it, as there are, to a greater or lesser extent, in the writer’s other books. In Green Hills of Africa, he recalls Cuba as a “long, beautiful, and unhappy island.” He would say somewhere: “I love this country and feel at home; and where a man feels at home, apart from the place where he was born, that is the place where he was destined.” He reiterated an idea when he learned he had won the Nobel Prize: “This is a Prize that belongs to Cuba, because my work was conceived and created in Cuba, with my people from Cojímar, where I am a citizen. This adopted homeland, where my books and my home are, is present throughout all the translations.”

After the publication of The Old Man and the Sea, Hemingway owed a debt to the fishermen of Cojímar, the small coastal town east of Havana. When the Modelo brewery in El Cotorro paid tribute to him for the Nobel Prize, those men were the guests of honor at the party. After the publication of the novel, he was definitely indebted to the island, and that perhaps explains his decision to offer the Prize medal to the Virgin of Charity of Cobre, Patron Saint of Cuba.

Agencies/ Lecturas/ Ciro Bianchi/ Internet Photos/ www.TheCubanHistory.com/ Arnoldo Varona.

THE CUBAN HISTORY, HOLLYWOOD.