CUBAN AIR FORCE PLANES: INFORMATION

Air and Air Defense Force (DAAFAR) are the primary agency handling planes and its flying and maintenance. Cuban air force owns many planes designed and manufactured by erstwhile Soviet Union and then Latin American countries. During 1980s, Cuba showed the air powers to countries in Africa with the help of Soviet Union. During this period Cuba dispatched many fighter planes to African countries such as Angola and Ethiopia to execute many aerial attacks on South Africa and Somalia respectively.

There are many aircrafts meant for attacking the enemies. These are L-39 and Mi-24. The Cuban air force has fighter planes such as MiG-21, MiG-23 and MiG-29, all of which are imported from Soviet Union. The Cuban air defense force has trainer planes such as L-39, which are being used extensively to train pilots of DAAFAR. The transport aircrafts the Cuban air force own include Mi-8, An-24 and MI-17.

Cuban Air force fighter planes which are in use include MiG-29UB. They had owned the Hawker Sea Fury, MiG-15, MiG-17, MiG-19, North American P-51 Mustang and North American B-25 Mitchell. It is estimated that at present Cuban air force has about 230 fixed wing aircrafts. There are thirteen military bases in Cuba. The Cuban air force planes are distributed and stationed at these stations. The exact picture of Cuban air force assets are not known to the open world.

A recent assessment in 2007 states that Cuban air force has 8000 personnel, 31 combat airplanes, and other 179 aircrafts. The 31 combat consist of 4 MiG-21s, 24 MiG-23s and 3 MiG-29s. Cuban air force planes also include transport aircrafts and helicopters for surveillance.

Defense specialists have different opinions on the strength and weakness of the Cuban air force and Cuban air force planes. Some believe that Cuban air force just possess bare minimum planes just enough to run the defense internally. The training facilities are also bare minimum. But some experts differ in this and believe that they have enough Cuban air force planes to tackle any internal and external threats.

Sources: Kwintess/InternetPhotos/TheCubanHistory.com

Cuban Air Force Planes

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

BIRTH OF AIR TRANSPORT IN CUBA

On 17 May 1913, Domingo Rosillo piloted an airplane from Key West, Florida to Cuba securing the $10,000 award for being the first to accomplish the feat. This 90-mile crossing came just ten years after the Wright brothers’ historic and four years after Blériot’s famous English-Channel crossing of twenty-one miles. Cubans rallied behind the achievement. As the stamps in fig. 1 depict, however, Agustín Parlá, a Cuban-born pilot who crossed the Straits two days after Rosillo with just a simple compass (Rosillo preferred a naval escort) acquired the more lasting recognition.

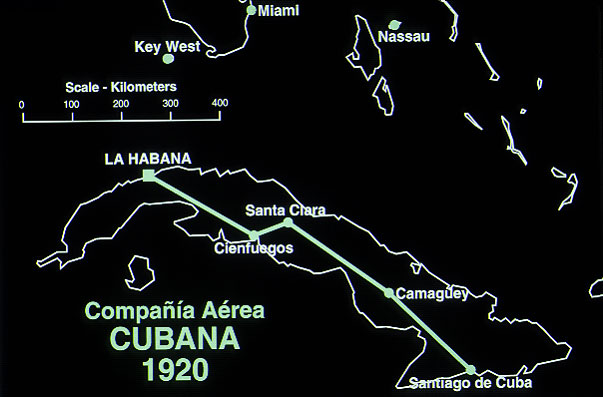

In October 1919, the Compañía Aérea Cubana (C.A.C) was founded by Hannibal J. de Mesa. He purchased six Farman aircraft, which a French team brought to Cuba by ship. C.A.C. began a flying school with Farman F-40s; it did some sightseeing around Havana; carried out surveying and aerial photography; and started a small . The General Manager was Agustin Parlá.

The first Cuban service started in October 1920 and although this enterprise survived for only a few months, it opened the first regular schedule in the whole of Latin America. Two weeks earlier, a United States company had opened an air link between Havana and the United States. These were bold experiments in the embryo stage of an industry that had yet to identify its role in society.

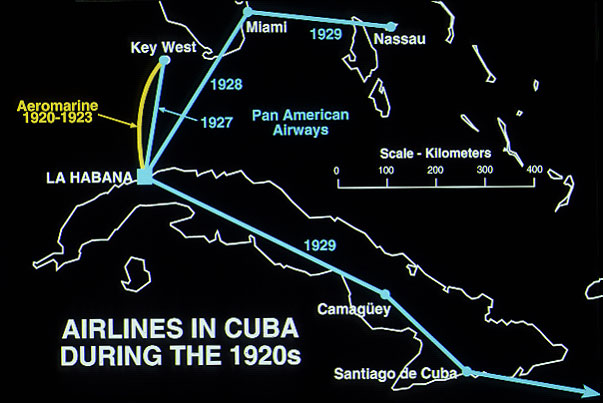

Meanwhile, in 1920, the Cuban aviator, Jaime González, was to make the first air mail in Cuba (fig. 2a), and on 15 October 1920, in the United States, Florida West Indies Airways (F.W.I.A.) received the first Foreign Air Mail contract from the U.S. Post Office (fig 3, fig 4, fig 5). One month later, Aeromarine, which had purchased F.W.I.A., began regular service from Key West to Havana using Curtiss Type F5L flying boats.

On 30 October 1920, C.A.C. had started Cuban domestic services, with Farman F-60 Goliaths on a new route from Havana to Santiago de Cuba, via Cienfuegos/Santa Clara and Camagüey. But on January 1921, this service ended, because of economic in Cuba, caused by big sugar beet harvests in Europe. By 1 Nov. 1921, Aeromarine was operating two daily Curtiss F5L services from Key West to Havana. But after about two years, Aeromarine also ceased operations, because of financial losses.

Sources: Smithsonian/Pichs/TheCubanHistory.com

BIRTH OF AIR TRANSPORT IN CUBA

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

WINSTON CHURCHILL IN CUBA.

The most curious events in the Spanish-Cuban-American war was the presence of Winston Churchill (1895) much before the U.S. entry into the war. Churchill was gathering information as a military observer. There are even some who infer that the information on tactics and methods used by the Spanish was put to work in subsequent Boer War, and led to the eventual victory of the British forces in that South African War.

It is interesting to speculate that a much more complete military style copy of Churchill’s reports may exist somewhere in the vast archives of the British Empire, or in the private papers of his son Randolph. In support of this, one can infer tantalizing hints by Randolph, when he refers to his father Winston Churchill’s advice to him at the time of the Spanish Civil War so as not to appear to be a spy. In addition, it is noted below Winston Churchill at the time of his visit to Cuba was on a leave of absence from his regiment.

However, one should bear in mind what a knowledgeable source points out (for further details see Davis 1906): “Churchill’s visit to the front was typical of ambitious British (and German, Japanese, Russian, Turkish, and even American) military officers of the day. They got experience in seeing combat, and the resulting reports filed at home could help boost one’s chances of promotion. In many cases it was also lucrative in that the observers would also write articles for popular magazines. The American and Spanish armies were loaded with observers. At times, however, the observers were not necessarily welcomed by their own units, who had to stand the boring times (with the lack of promotion) at home, while the officers of means could get a leave of absence and go gallivanting.”

What we see below are accounts by a brilliant, but still very young, man who just turning twenty-one as yet does not fully understand the complexities of irregular war, nor the subtleties of Cuban politics and racial relations. For instance Churchill accepts the Spanish propaganda point that Antonio Maceo was a Black separatist, a while it is now clear that Maceo, not only was not completely black (he was mulatto), but was an avowed integrationist. The Spanish (e.g. Antonio Serra Ortiz, 1906) view of the war was of course quite different from the Cuban perspective (Jose Miro Argenter 1909). Whatever, South Africa, the Sudan, Gallapoli etc, will teach Churchill other lessons, and a great man will be forged.

Sources:Daley/InternetPhotos/TheCubanHistory.com

WINSTON CHURCHILL IN CUBA

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

TIMELINE IN CUBA HISTORY (1868-1961)

1868-78 First war of Cuban independence. Also known as the Ten Years’ War.

1868 October 10 , Revolutionaries under the leadership of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes proclaims Cuban independence.

1878 February 8, Pact of Zanjón ends Ten Years’ War and ends uprising.

1879 August, A second uprising (“The Little War”), engineered by Antonio Maceo and Calixto García, begins but is quelled by superior Spanish forces in autumn 1880.

1886 Slavery abolished

1890 February, José Sánchez Gómez becomes provisional Governor of Cuba.

1895 23 February Mounting discontent culminated in a resumption of the Cuban revolution, under the leadership of the writer and patriot José Martí and General Máximo Gómez y Báez.

1895 May 19 José Martí killed in battle with Spanish troops at the Battle of Dos Ríos.

1895 September, Arsenio Martínez Campos is defeated at Peralejo and leaves Cuba in January next year.

1896 Successful invasion campaign along the length of the island by Cuban rebels led by Antonio Maceo, and Maximo Gomez; Winston Churchill fights on Spanish side at battle of Iguara [1]; Maceo is killed on return east [2]

1897 Calixto Garcia takes a series of strategic fort complexes in the East and the Spanish are essentially confined to coastal cities there.

1898 June 6–10th Invasion of Guantánamo Bay American and Cuban forces invade the strategically and commercially important area of Guantanamo Bay during the Spanish-American war.

1898 March 17, U.S. Senator, and former War Secretary Redfield Proctor protests against Spanish controlled concentration camps

1898 December 10, Treaty of Peace in Paris ends the Spanish-American War by which Spain relinquished sovereignty over Cuba.

1899 January 1, The Spanish colonial government withdraws and the last captain General Alfonso Jimenez Castellano hands over power to the North American Military Governor, General John Ruller Brooke.

1899 December 23 Leonard Wood becomes US Provisional Governor of Cuba

Republican Cuba

1901 March 2, Platt Amendment passed in the U.S. stipulating the conditions for the withdrawal of United States troops, assuring U.S. control over Cuban affairs.

1902 May 20 The Cuban republic is instituted under the presidency of Tomás Estrada Palma.

1906 September 29 Revolt against Tomás Estrada Palma successful. Peace negotiated by Frederick N. Funston, U.S. troops reoccupy Cuba under William Howard Taft.

1906 October 13 Charles Magoon becomes U.S. governor of Cuba

1909 January 28 Cuba returns to homerule. José Miguel Gómez of the Liberal Party becomes president.

1912 Separatist Black revolt is defeated in bloody campaign

1913 May 20 Mario García Menocal presidency begins.

1917 April 7 Cuba enters World War I on the side of the Allies. In Chambelona War Liberal Revolt is suppressed by Conservadores of Menocal

1921 May 20 Alfredo Zayas becomes president.

1925 May 20 Gerardo Machado becomes president. At uncertain date Fabio Grobart, a stalinist communist leader enters Cuba

1926 August 13 Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz born in the province of Holguín.

1928 June 14 Ernesto Guevara de la Serna (Che Guevara) born in Rosario, Argentina.

1928 January 10 Julio Antonio Mella a founder of the Stalinist Communist Party in Cuba is murdered in Mexico. Details are murky; Gerardo Machado agents blamed by some, Tina Modotti and Vittorio Vidale communist assassins blamed by others.

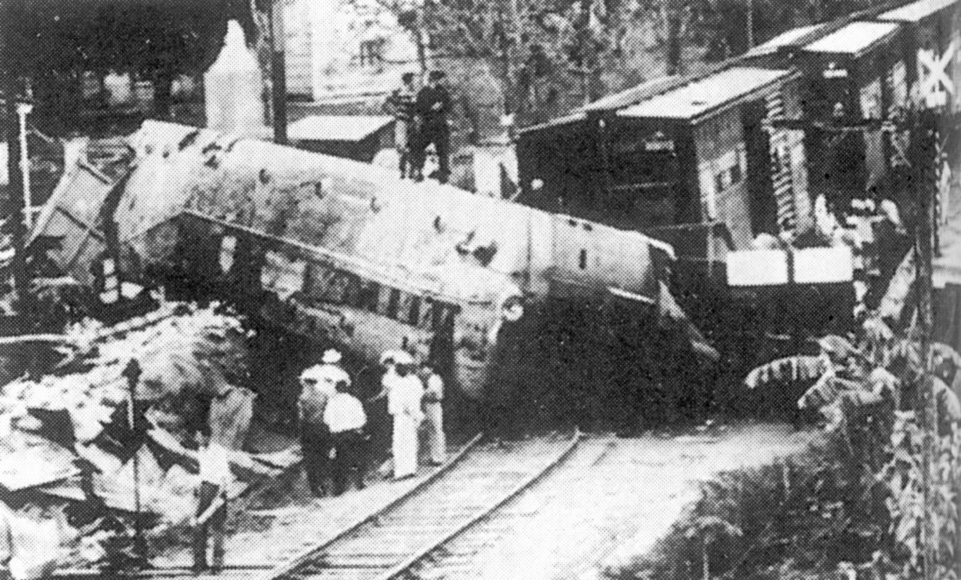

1931 August 10–14 Old Mambi warriors Carlos Mendieta and Mario García Menocal land forces at Rio Verde attempting to overthrow the now clearly dictatorial Gerardo Machado. They are defeated in actions that include first military aviation use in Cuba.

1933 August 12 Gerardo Machado, despite last minute support from the Communist Party, is forced to leave Cuba, by ABC and Antonio Guiteras Holmes resistance actions, a general strike, pressure from senior officers of Cuban Armed Forces and U.S. Ambassador Sumner Welles. Communist activity high and extends through rest of summer with establishment of ephemeral soviets in eastern provinces.

1933 September 4 “Sergeants’ Revolt” organized by a group including Fulgencio Batista topples provisional government.

1933 October 2 Batista loyal enlisted men and sergeants, plus radical elements, force Army Officers out of Hotel Nacional in heavy fighting. Some are murdered after surrender.

1933 November 9 Blas Hernández his followers and some ABC members make a stand in old Atarés Castle they are defeated by Batista loyalists in bloody battle and Blas Hernández is murdered on surrender.

1934 June 16, 17 1934 ABC demonstration Havana festival and march attacked by radical gunners including those of Antonio Guiteras with bombs and machine guns, numerous dead.

1935 May 8 Leading radical Antonio Guiteras is betrayed and dies fighting Batista forces.

1938 September Communist party legalized again.

1939 after August 23 Fabio Grobart publicly justifies Ribbentrop-Molotov pact.

1941 May 8, 1941 Sandalio Junco, a Communist labor leader who defected to Trotskyism, is murdered by Stalin Loyalists.

1941 December Cuban government declares war on Germany, Japan, and Italy.

1943 Soviet embassy opened in Havana.

Revolution and Socialist Cuba

1951 May 15 Eduardo Chibás, leader of the Ortodoxo party and mentor of Fidel Castro commits suicide on live radio.

1952 March Former president Batista, supported by the army, seizes power.

1953 July 26 Some 160 revolutionaries under the command of Fidel Castro launch an attack on the Moncada barracks in Santiago de Cuba. Communists at meeting in Santiago arrested, Fabio Grobart said to have attended, but not listed in arrest records,

1953 October 16 Fidel Castro makes “History Will Absolve Me” speech in his own defense against the charges brought on him after the attack on the Moncada Barracks.

1954 September Che Guevara arrives in Mexico City.

1954 November Batista dissolves parliament and is elected constitutional president without opposition.

1955 May Fidel and surviving members of his movement are released from prison under an amnesty from Batista.

1955 June Brothers Fidel and Raúl Castro are introduced to Che Guevara in Mexico City.

1956 April 29 Autentico Assault on Goicuria Barracks, in Matanzas attackers are ts including Raúl Castro, Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos, executes informers and sets sail from Mexico for Cuba on the yacht Granma.

1956 December 2 Granma lands in Oriente Province.

1957 January 17, Castro’s guerrillas score their first success by sacking an army outpost on the south coast, and start gaining followers in both Cuba and abroad.

1957 March 13, University students mount an attack on the Presidential Palace in Havana. Batista forewarned. Attackers mostly killed, others flee and are betrayed.

1957 May 28 1957, Castro’s 26 July movement, heavily reinforced by Frank Pais Militia, overwhelm an army post in El Uvero.

1957 July 19 Autentico landing in the “Corynthia,” led by Calixto Sánchez White in north Oriente, at Cabonico Batista is forewarned and then guided by agents, almost all 27 killed.

1957 July 30 Cuban revolutionary Frank País is killed in the streets of Santiago de Cuba by police while campaigning for the overthrow of Batista government.

1957 September 5 Naval revolt at Cienfuegos is crushed by forces loyal to Batista.

1958 February Raúl Castro takes leadership of about 500 pre-existing Escopeteros guerrillas and opens a front in the Sierra de Cristal on Oriente’s north coast.

1958 March 13 U.S. suspends shipments of arms to Batista’s forces.

1958 March 17 Castro calls for a general revolt.

1958 April 9 A general strike, organized by the 26th of July movement, is partially observed.

1958 May Batista sends an army of 10,000 into the Sierra Maestra to destroy Castro’s 300 armed guerrillas (supported by uncounted escopeteros). By August, the rebels had defeated the army’s advance and captured a huge amount of arms.

1958 November 1 A Cubana aircraft en route from Miami to Havana is hijacked by militants but crashes. The hijackers were trying to land at Sierra Cristal in Eastern Cuba to deliver weapons to Raúl Castro’s rebels. It is the first of what was to become many Cuba-U.S. hijackings.[2]

1958 November 20 to November 30 Key position at Guisa is taken, and in the following month most cities in Oriente fall to Rebel Hands.

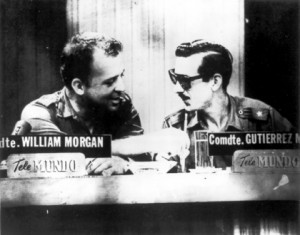

1958 December Guevara, William Alexander Morgan and non-communist Directorio Forces attack Santa Clara.

1958 December 28 Rebels seize Santa Clara.

1958 December 31 Camilo Cienfuegos leads revolutionary guerrillas to victory in Yaguajay, Huber Matos Enters Santiago.

1959 January 1 President Batista resigns and flees the country. Fidel Castro’s column enters Santiago de Cuba. Raul Castro starts mass executions of captured military. Diverse urban rebels, mainly Directorio, seize Havana

1959 January 2 Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos arrive in Havana.

1959 January 5 Manuel Urrutia named President of Cuba

1959 January 8 Fidel Castro arrives at Havana, speaks to crowds at Camp Columbia.

1959 February 16 Fidel Castro becomes Premier of Cuba.

1959 March Fabio Grobart is present at a series of meetings with Castro brothers, Guevara and Valdes at Cojimar

1959 April 20 Fidel Castro speaks at Princeton University, New Jersey.[3]

1959 May 17 The Cuban government enacts the Agrarian Reform Law which limits land 1,000 acres (4.0 km2) ranches or less if other agricultural land, no payment is made.

1959 July 17 Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado becomes President of Cuba, replacing Manuel Urrutia forced to resign by Fidel Castro. Dorticós serves until 2 December 1976

1959 October 28 Plane carrying Camilo Cienfuegos disappears during a night from Camagüey to Havana. He is presumed dead.

1959 December 11, Trial of revolutionary Huber Matos begins. Matos is found guilty of “treason and sedition”.

1960 March 4, the freighter La Coubre a 4,310-ton French vessel carrying 76 tons of Belgian munitions explodes while it began unloading in Havana harbor.

1960 March 17, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower orders CIA director Allen Dulles to train Cuban exiles for a covert invasion of Cuba.

1960 July 5 All U.S. businesses and commercial property in Cuba is nationalized at the direction of the Cuban government.

1960 October 19, U.S. imposes embargo prohibiting all exports to Cuba except foodstuffs and medical supplies.

1960 October 31, nationalization of all U.S. property is completed.

1960 December 26, Operation Peter Pan (Operación Pedro Pan) begins, an operation transporting 14,000 children of parents opposed to the new government. The scheme continues until U.S. airports are closed to Cuban during 1962.

1961 January 1, Cuban government initiates national literacy scheme.

1961 “March” former rebel comandante Humberto Sorí Marin and Catholic leaders shot.

1961 April 15, Bay of Pigs invasion.

1961 US Trade embargo on Cuba.

Sources: Wikepedia/TheCubanHistory.com

TIMELINE IN CUBA HISTORY (1868-1961)

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

SPANISH AMERICAN WAR IN CUBA

Cuba Struggle for Independence (1868-1898)

and then (Washington Post published), starts the “Splendid Little” War . What follows are some benchmarks along the way:

April 10, 1895 — Jose Marti, Cuban revolutionary, launches insurrection against Spanish rule. He is killed May 19.

Jan. 1, 1898 — In an effort to defuse the insurrection, Spain gives Cubans limited political autonomy.

Jan. 12 — Spaniards in Cuba riot against autonomy given to Cubans.

Jan. 25 — USS Maine arrives in Havana Harbor to protect American interests.

Feb. 15 — USS Maine explodes, sinks; 266 crewmen lost. The Maine’s captain urges suspension of judgment on the cause of the explosion.

March 28 — Naval Court of Inquiry says Maine destroyed by a mine.

April 11 — President William McKinley asks Congress for declaration of war.

April 25 — State of war exists between United States and Spain.

June 10 — U.S. Marines land at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

July 1 — Battles of El Caney and San Juan Hill in Cuba result in American victories and instant national acclaim for Lt. Col. Theodore Roosevelt, the former Navy Department official and future president who leads the Rough Riders at San Juan Heights.

July 3 — Spain’s Atlantic fleet, having sought refuge in the harbor of Santiago, Cuba, attempts to escape and is destroyed by American naval forces.

July 6 — Congress, caught up in expansionist fever fed by the war, votes to annex Hawaii, which has nothing to do with Spain.

July 14 — Santiago surrenders. Yellow fever breaks out among American troops the next day.

July 25 — U.S. Army invades Puerto Rico.

July 26 — Spain asks for peace.

Aug. 6 — Spain accepts American terms for peace.

Aug. 12 — Truce is signed with Spain.

Oct. 1 — Peace negotiations with Spain commence in Paris.

Dec. 10, 1898 — War ends, officially, with signing of the Treaty of Paris (With no Cuban Representative present). United States pays Spain $20 million for Philippines. Spain also cedes Puerto Rico and Guam and agrees to renounce sovereignty over Cuba.

In 1902, the U.S. declares Cuba independent, keeps naval base and the right to intervene in internal and foreign affairs (EmmPlatt).

WashingtonPost/EugeneMeyer/InternetPhotos/TheCubanHistory.com

Spanish American War

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

CUBAN HEROES: BERNABE VARONA BORRERO

Cuban patriot. Born in 1845 in Camagüey and died in 1873 in Santiago de Cuba.

In his hometown took part in the work that gave rise to conspiracy in the region uprising against the colonial power in November 1868 and was one of the first to take up arms to join the patriots of Bayamo. Noted for his courage and determination, he was appointed chief of the bodyguard of President Carlos Manuel de Cespedes.

In May 1869 he was responsible for the burning of Guaimaro city where a month earlier had been agreed the first Constitution of the Republic in arms, and whose defense was impossible because of powerful siege to the Spanish forces. In June of that year he participated in the attack on Las Tunas. He fought in Las Minas and mares, and was among the attackers of Fort St. Joseph. In 1869 he rescued, head of fourteen men, a Cuban family that was driven toward prisoner Camaguey, a Spanish column of more than three hundred members.

In April 1871 he was sent abroad with a mission to organize expeditions to support the insurrection.

On 23 October 1873, the Virginius sailed from Kingston, Jamaica with a large number of Cuban insurgents (102 according to our count). The ship sailed to Jeremie on the island of Haiti and from there to Port-au-Prince, where 300 Remingtons and 300,000 cartridges were loaded on-board. From Port-au-Prince the Virginius went to Comito, where 800 daggers, 800 machetes, a barrel of powder and a case of was loaded. The steamer, which at this time was leaking, headed for Cuba, but never reached shore. About six miles from land, with the hills of Guantanamo in sight, the Virginius was intercepted by the Spanish warship Tornado, under the command of Captain Dionisio Costilla (the Tornado, coincidentally had been built at the same Scottish shipyard for the Chilean navy and had been captured by a Spanish frigate during the Pacific War between Chile and Peru and incoporated into the Spanish Armada under the same name) .

The Virginius then turned course to Jamaica and an 8-hour sea chase ensued. During this chase, guns and equipment were dumped overboard to lighten ship, but the poor physical condition of the ship and engines caused Captain Fry to stop and surrender the ship barely 6 miles from the Jamaican coast on 31 October 1873 (some reports indicate that the ship was already within British territorial waters).

The Virginius was towed by the Tornado to Santiago de Cuba harbor and arrived on 1 November 1873. On board were a total of 165 persons (154 according to our count), including the ship’s crew and an expeditionary force intending to aid the Cuban revolutionary cause. In charge of the expedition was the General Bernabe Varona y Borrero, seized by the colonial authorities, was one of the fifty-three men were shot on that occasion.

In the Santa Efigenia cemetery of Santiago de Cuba there is a small rectangular pantheon, with a royal palm in each of its corners, where the victims of the Virginius are buried. There is a plaque in memory of the victims.

Marti made reference to his heroism in the note “Bernabe Varona’s mother,” published in Patria , on January 26, 1895.

Sources:CamagueyanosCuba/CubaGenWeb/InternetPhoto/TheCubanHistory.com

BERNABE VARONA BORRERO

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

THE CIA’s MAN AT THE BAY OF PIGS.

The three days of futile bloodshed haunted the both of them — the CIA spook and the commander in chief he despised, John F. Kennedy.

”We both had scores to settle with Castro,” the old, bullet-scarred commando recalls from his home in Tampa. ”But I wasn’t haunted in the same way that Kennedy was. I had nothing to feel guilty about.”

Such is Grayston L. Lynch’s way of explaining his long, strange bond to a flawed president and a lost cause that began 37 years ago with the bloody, tragic, history-altering Bay of Pigs invasion and continued until 1967 in more than 2,000 secret CIA raids on Cuba from Miami.

Lynch was our man on Cuba’s Playa Giron beach on April 16, 1961 — the white, ”Tex-Mex”-speaking CIA agent who fired the first shot of the Bay of Pigs assault and then took desperate, unofficial command of the doomed force of 1,500 Cuban volunteers, most of them Miami exiles, recruited and trained — then disavowed — by the Kennedy administration.

Sunday, at age 75, Lynch returns to Miami with a new book that vents bitterness and disillusionment, but celebrates the bravery of his comrades in arms, about 75 of whom died, and 1,250 of whom were captured and imprisoned.

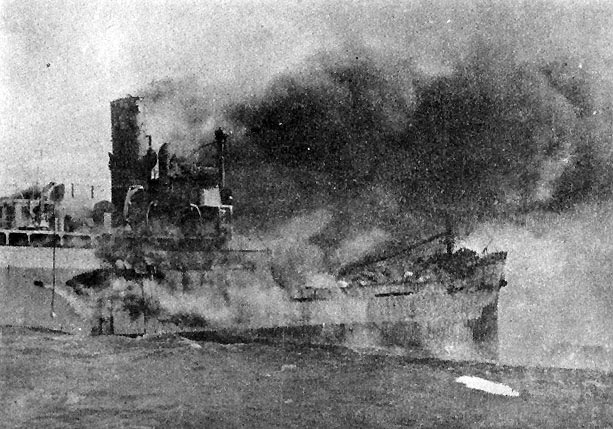

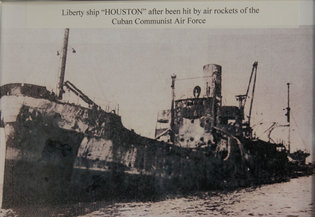

Many of them are now prominent and successful Americans — including Miami’s former state Rep. Luis Morse, House Speaker pro tempore, then in command of the supply ship Houston. Lynch describes Morse’s desperate beaching of the Houston in the Bay of Pigs after Cuban warplanes blew a 10-foot hole in its stern.

Lynch hasn’t seen any of the survivors of the 2506 Assault Brigade in years, but the Cuban volunteers who made up the force regard him as ”one of the big warriors of this country,” says Jose Dausa of the 2506 Brigade Association in Miami.

In his book, Decision for Disaster: Betrayal at the Bay of Pigs (Brassey’s, $24.95), Lynch returns the compliment: ”The only heartening observation . . . was that the brigade had fought magnificently. Outnumbered in every battle by at least twenty to one, it had inflicted heavy casualties on Castro’s forces at a rate of fifty to one.”

Much about the Bay of Pigs debacle — a three-day battle that failed after President Kennedy canceled air support and disavowed American involvement — already has been told in other books.

But the mere fact that Lynch is alive and intact to tell his bullet-whizzing, ground-zero tale, which he wrote more than 20 years ago and only now has published, seems miraculous.

War wounds

He carries wounds from World War II’s D-Day Normandy invasion, from the Battle of the Bulge, and from Heartbreak Ridge in Korea. He served with the Special Forces in Laos. After the Bay of Pigs disaster until 1967, Lynch directed 2,126 clandestine CIA assaults on Cuba out of Miami, directly participating in 113 of them.

This week, Lynch said he never worked with Luis Posada Carriles, whom The New York Times recently identified as a Miami-based bomber financed by the late to conduct raids against Cuba in the mid-1960s.

But Lynch himself ducked ”a thousand” Cuban bullets from 1960 to 1967, and eventually adopted a custom of the Cuban exiles he commanded — he wore a Catholic Virgin de Cobre medallion around his neck to keep him from harm. ”There must have been something to it,” he now laughs.

Must have been. In his 1979 book, Bay of Pigs, author Peter Wyden describes Lynch as a real-life lethal weapon who ”moved well and cursed sparingly . . . Hollywood could not have cast a better personality. [Lynch] suggested what the operation needed most: indestructibility.”

Lynch is the surviving half of a two-man, non-Cuban CIA team which the Kennedy administration attached to the Brigade. The other agent, William ”Rip” Robertson, died in 1973 of malaria in Laos.

Both agents, vaguely assigned to the 2506 Brigade as ”troubleshooters,” ended up going ashore and fighting. Gray accompanied a night team of frogmen to Playa Giron and actually started the battle by firing on a Cuban jeep that directed its headlights at the frogmen as they rafted in. (They learned later that the militia members in the jeep thought they were lost fishermen.)

After returning to his supply ship, the Blagar, Gray later shot down two Cuban warplanes and, in Wyden’s words, ”became the closest thing to an on-the-spot military commander that the Cuban operation ever had.”

Like Armageddon

So chaotic was the battle that at one point, when one of the Brigade’s supply ships was destroyed by Cuban attack planes, some believed that Armageddon itself beckoned.

Lynch recalls:

”The Rio Escondido exploded in a huge, mushroom-shaped fireball. . . . At this moment, I received an urgent call from Rip up at Red Beach. . . . ”Gray!” Rip said. ”What the hell was that?” I told him that the Rio Escondido had been hit and had exploded. ”My God, Gray! For a moment, I thought Fidel had the A-bomb!”

Lynch asserts that Cuban ground defenses ”were kind of like a mob, coming at us in open trucks while we blasted away,” and the invasion would have wildly succeeded if not for the aerial bombardment.

The bombings caused panic aboard the remaining supply ships, mostly operated by civilian crews, which fled to sea, and left the Brigade without ammunition.

Lynch includes this last dispatch from Brigade commander Jose ”Pepe” San Ramon:

”Tanks closing in on Blue Beach from north and east. They are firing directly at our headquarters. Fighting on beach. Send all available aircraft now!”

And finally:

”I can’t wait any longer. I am destroying my radio now.”

All of this tragedy Lynch attributes to Kennedy’s last-minute decision to cancel air strikes, fearful of widening U.S. involvement.

”This may have been the politically proper way to fight a war, according to the rules laid down by the ‘armchair generals’ of Camelot,” Lynch writes, ”but we called it murder.”

Rescuing survivors

The one honorable U.S. aspect of the failed invasion, he says, was the Navy’s full-scale effort afterward to rescue survivors.

He describes this scene:

”The search planes reported a survivor sitting under a mangrove tree, slowly waving a white cloth on the end of stick . . . He’d been drinking salt water and could neither stand nor talk . . .

”Slowly, drop by drop, we were trying to get water into him . . . Finally, he was able to form a few words.

”I asked what the man had said. Turning to me with tears in his eyes, [frogman Amado] Cantillo said, ‘He wants to know if we won.’ ”

Despite Lynch’s contempt for Kennedy, the agent believes Kennedy’s subsequent secret campaign against Castro — which brought to Miami the largest CIA contingent outside of Langley, Md. — was devastatingly successful and would have toppled Castro if not for Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. He plans to publish a second book about those Miami years, tentatively titled The CIA’s Secret War on Cuba.

Sunday he’s looking forward to signing books for any Brigade veterans who come to his reading — men he last knew only as ”brave boys who had never before fired a shot in anger.”

But Miami, he says, is as close to Cuba as he ever wants to get — even if he outlives Castro, which he’s not betting on. ”I’ve already seen Cuba,” he says.

Sources:MiamiHerald/JohnBarry/TheCubanHistory.com

THE CIA’s MAN AT THE BAY OF PIGS.

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

SEARCHING FOR “CHE” GUEVARA ‘DEAD OR ALIVE’ (I)

In early 1965, the CIA began to hear whisperings of Che’s plan to export the Castro Revolution — he considered it Cuba’s duty to encourage other “national liberation movements” around the world. CIA officials immediately put Gustavo Villoldo and other Cuban Americans on the scent.

This is the CIA agent who hunted Che.

It was Villoldo who hounded him from the Caribbean to Africa to Latin America to avenge his father’s death and fight Castro’s brand of communism.

Villoldo crossed a river in the dead of night to infiltrate the leftist side of a bloody civil war in the Dominican Republic to check out rumors that Che was there. The Argentine was nowhere to be found.

He led a group of Cuban-American CIA agents into the Congo later that year, just missing Che as he escaped to neighboring Tanzania with 120 other Cubans after the government squashed rebel forces.

“We had him identified there and were there for 28 days, but all was lost for Che already, and he escaped,” said Villoldo. “A few more days and we might have closed in on him.”

His CIA orders were to locate Che, Villoldo recalled, “but my intention was to get him, dead or alive.”

Che went into hiding for months after the Congo, licking the wounds to his fighting psyche and searching for another country where he could try his hand at subversion. After discussions with Castro, he settled on Bolivia.

Che lasted barely 12 months in the jungles of Bolivia, the first eight in hiding while preparing his guerrilla campaign, the last four running from a battalion of Bolivian Army Rangers, trained by U.S. Army Green Berets and advised by a team of three Cuban exiles working for the CIA. A CIA official who directed the Bolivia mission has confirmed that Villoldo was the “lead agent in the field.”

Two of the three CIA men, radio operator Felix Rodriguez and urban police adviser Julio Garcia, later were featured in books that gave their own, sometimes embellished stories on the hunt for Che.

But the team’s leader, Villoldo, has kept his version of events to himself, until now.

Villoldo carried Bolivian army credentials identifying him as Capt. Eduardo Gonzalez. He wore Bolivian army fatigues and was so discreet that several Bolivian officers who worked with him for several weeks never realized he was a CIA man.

Among his tasks: evaluating information from the interrogation of French socialist Regis Debray, who had written a glowing book on the Castro guerrillas’ ideology. Debray had been captured after visiting Che in the Bolivian jungles.

In an ugly dispute that continues to this day, Che’s family has accused Debray of betraying him. Debray denies it. Said Villoldo, using Cuban slang for someone who confesses all: “He talked through his elbows.”

Che, 39, was wounded and captured during a jungle firefight on Oct. 8, 1967. He was executed by two Bolivian Rangers the next day in the mud-brick schoolhouse in the village of La Higuera, on orders from Bolivia’s military dictator, Rene Barrientos.

“At no time did I or the CIA have a say in executing Che,” said Villoldo. “That was a Bolivian decision.”

Che’s corpse was strapped to the skids of an army helicopter on Oct. 9 and flown to the nearby farm town of Vallegrande, where the Rangers tracking Che had set up a base near an airstrip. The body was displayed for peasants and journalists for the next 24 hours, on a stretcher placed atop a cement washstand in the laundry room of Our Lord of Malta Hospital, really a lean-to attached to the back of the hospital. And then it disappeared for 30 years.

Sources: Herald/Tamayo/Villoldo/TheCubanHistory.com

SEARCHING FOR “CHE” GUEVARA ‘DEAD OR ALIVE’ (I)

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

SEARCHING FOR “CHE” GUEVARA ‘DEAD OR ALIVE’ (II)

Gary Prado, the captain who commanded the Ranger company that captured Che, and who later rose to the rank of general, insisted for years that the body had been cremated and the ashes scattered. Others whispered that it was thrown from a helicopter into the deepest jungle, or fed to wild dogs.

But then in late 1995, retired Bolivian Gen. Mario Vargas told American author John Lee Anderson, who was writing a Che biography, that the body had been buried near the Vallegrande airstrip. Vargas later admitted he had based his story on hearsay — which happened, ironically, to be correct.

Suddenly, the little town of 8,000 people was awash in Cuban forensic anthropologists and geologists. They managed to locate five remains, only a fraction of the 32 guerrillas, including Bolivian and Peruvian leftists and Cuban Sierra Maestra veterans, killed in the area in 1967 and buried in unmarked graves.

But for the next 16 months there was no sign of Che’s body. And Che, for all the Cubans’ talk of the importance of giving proper funerals to all of the dead guerrillas, was the real prize.

And then this spring, Gustavo Villoldo surfaced and made a bombshell offer.

In an April 23 message clandestinely delivered to Che’s daughter Aleida, a Castro supporter living in Havana, Villoldo offered to personally dig up Che’s remains and turn them over to her for humanitarian reasons.

Villoldo wrote that only two years earlier, he had believed that Che’s body should remain hidden. But several factors, he added, had led him to “a profound reconsideration.”

“I have not renounced the personal, ideological and political principles that drove me to fight against Ernesto `Che’ Guevara,” he wrote Aleida. “But in the same way the United States wants back its dead in Korea and Vietnam, Guevara’s widow and children have the right to demand his body.”

He set two conditions:

No politics or propaganda, because he did not want to expose himself to attacks by exiles in Miami who might begrudge his decision to cooperate. “I am a political exile and live in a very difficult society of exiles, loaded with multiple pressures.”

And he wanted sole control over all publicity proceeds. Any profits derived from the fanfare almost certain to erupt, he said, should be donated to scholarships for Bolivian medical students.

Villoldo now acknowledges he had another concern in mind: Since it was likely that Che’s bones would eventually be recovered — after all, the Cubans were digging in the correct area — injecting himself into the excavations would take the edge off Castro’s likely triumph. “There were still politics and propaganda involved, and I still did not want Castro to capitalize completely on this,” he said.

Cuban officials would later charge that Villoldo was only trying to throw the search off-track, and would attack his demand to control all publicity as a crass effort to capture the limelight and cash in on Che’s bones.

But Villoldo’s offer in fact unleashed a race for the remains between the Cubans, Villoldo and even Bolivians who wanted to keep Che’s grave in Vallegrande as a tourism draw and political memorial.

“I was told Fidel pitched a fit because he could not allow the gusano [exile worm] who advised the Bolivian army in the hunt for Che, and the man who he knew had buried Che, to be the man who returned him to Cuba.”

Meanwhile, Vallegrande municipal officials declared Che’s remains a “national patrimony” and slapped a moratorium on digging until mid-June. Then the town started promoting a “Che’s Route” walking tour at $70 per day and planning a museum.

Loyola Guzman, who as a young woman was treasurer of the Bolivian Marxist faction that followed Che into the jungles, argued that if Che gave his life for Bolivia, his remains rightly belonged under Bolivian soil. “His life was an example of heroic internationalism that no single country should monopolize,” said Guzman, now a human-rights campaigner.

Villoldo meanwhile had hired a South Florida firm whose ground-search radar could locate Che’s burial site in case Villoldo’s memory failed him, contacted a book agent and negotiated with a three-man TV crew in Miami to record his search.

He denies that he wanted publicity for himself. “I wanted history to know exactly how things happened,” he said.

Villoldo had made reservations on a June 26 from Miami to Bolivia, and after much lobbying, won permission to search from Bolivian Human Resources Minister Franklin Anaya, a former ambassador in Havana and author of a sympathetic book on Cuba who was acting as the Bolivian liaison with the Cuban anthropologists. “I had my bags packed,” said Villoldo.

Media accounts later alleged that Anaya and Bolivian President Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada had made a deal with Castro to favor the Cuban team.

The accounts could not be confirmed, but Anaya suddenly canceled Villoldo’s plane reservations. Villoldo appealed to President Sanchez de Lozada and was again cleared to fly to Bolivia. But Bolivian friends counseled him to stay in Miami, Villoldo said.

“My friends told me that Castro knew of my planned arrival, and that there was some possibility the Cubans would take some action against me,” Villoldo said. “Based on the warning . . . I decided to wait and see what happened.”

What happened was a Cuban dash to find the body.

Just 18 days after Villoldo’s letter reached Aleida Guevara, and one day after the municipal ban on digging ended, the Cubans launched a search for Che’s remains with an intensity unseen in the previous 16 months of digging. They worked from sunup to sundown, virtually nonstop. They were in such a hurry, they used the one excavation tool considered anathema by all experts in their field — a bulldozer.

By June 27, a Cuban team led by Jorge Gonzalez, head of the Havana Institute of Legal Medicine, had dug several test trenches and pits in the area described by Gen. Vargas, but came up empty-handed. Time was running out.

President Sanchez de Lozada’s government had ordered all digging stopped on June 28, apparently because of the June 2 election of a new Bolivian president, Hugo Banzer. A former military dictator in the 1970s, Banzer is known to have little liking for Che, Castro or Cuba. Sanchez de Lozada might have correctly presumed his actions might come under unsympathetic examination by his successor.

Indeed, Banzer, sworn into office in August, has vowed to investigate his predecessor’s role in helping Cuba dig up Che’s remains, and to investigate press reports that Anaya might personally profit from the publicity rights to the excavation story.

No Hands

The Cuban diggers met until 4 o’clock the morning of June 28 to decide where to focus their last day of digging, recalled Alejandro Inchaurregui, one of a team of Argentine Forensic Anthropologists called in to help the Cubans.

What are believed to be the long-lost bones of Che rest on an examining table at a small hospital in Santa Cruz, Bolivia, on July 8 of this year.

Ground radar surveys conducted by the Cuban-Argentine search team in early 1997 had revealed a dozen spots of disturbed earth that could be secret grave sites — or maybe displaced rocks or fallen trees. Of these, three in particular had all the characteristics of being man-made. This is where they set to work. With a bulldozer.

In the first spot, they set the bulldozer blade to scrape away four inches of dirt with each pass. Nearly two hours later, they hit rock and no sign of any bones. They moved on to spot No. 2.

Eighteen scrapes of the bulldozer later, almost exactly six feet down, the blade uncovered and broke parts of a human skeleton.

What the Cubans had found were seven bodies, in two groups of three and four, separated by 2 1/2 feet, buried in a pit wedged between Vallegrande’s old dirt airstrip to the north and the nearby cemetery to the south.

Jubilation erupted when the second body was uncovered, the middle one in the group of three, and was found to have no hands. Che’s hands were amputated after his death as proof of his demise.

But Che’s remains still had to be officially identified by Bolivian government officials so that they could be released and flown to Cuba.

“Ministry of Interior people were telling us to move fast. As the inauguration of Banzer approached, the screws tightened,” said Inchaurregui.

And so in the dead of night on July 5, a convoy of 10 vehicles made a five-hour, 150-mile dash at breakneck speeds along treacherous mountain roads to transfer the remains to the provincial capital of Santa Cruz.

There, the handless remains were quickly identified. The excavated teeth perfectly matched a plaster mold of Che’s teeth made in Havana before he left for the Congo so that he could be identified if he died in combat.

And there was a clincher, revealed to Tropic by Jaime Nino de Guzman, who had been a Bolivian army major and helicopter pilot in 1967, and who had seen Che alive as a captive in La Higuera as he flew officers and supplies in and out.

Che looked dreadful, Nino de Guzman recalled last month from his home in La Paz. He was shot through the right calf, his hair was matted with dirt, his were shredded, and his feet were covered in rough leather sheaths. But Che held his head high, looked everyone straight in the eyes and asked only for something to smoke. Seldom seen without a Cuban cigar in hand after Castro triumphed, Che had switched to a pipe for the guerrilla war.

“I took pity, he looked so terrible, and gave him my small bag of imported tobacco for his pipe. He smiled and thanked me,” the pilot recalled in a telephone interview.

Thirty years later, Inchaurregui said, he was inspecting a blue jacket dug up next to the handless remains when he found a tiny inside pocket, almost hidden and apparently missed by the soldiers who searched Che’s body. Tucked away inside was a small bag of pipe tobacco.

“I must tell you I had serious doubts at the beginning. I thought the Cubans would just find any old bones and call it Che,” said Nino de Guzman. “But after hearing about the tobacco pouch, I have no doubts.”

Neither do most others familiar with the search.

“Just seeing the genuine excitement, the genuine euphoria on the face of the Cubans there makes me certain this was Che’s remains,” said John Lee Anderson, the American author. Anderson witnessed the final stages of the dig. “They were simply overcome, crying and hugging each other.”

Sources: Herald/Tamayo/Villoldo/TheCubanHistory.com

SEARCHING FOR “CHE” GUEVARA ‘DEAD OR ALIVE’ (II)

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

SEARCHING FOR “CHE” GUEVARA ‘DEAD OR ALIVE’ (III)

Recovering Che’s remains was a propaganda triumph for Castro, whose ideology has all but keeled over since the collapse of the Soviet Bloc.

Che was, literally, the poster boy for the Cuban Revolution. He was an asthmatic, Argentine-born physician who joined Castro in the war against the Batista dictatorship, then rejected Soviet orthodoxy, and gave his life trying to export an ideology that he regarded as more humanitarian than communist. A 17-ton, five-story steel profile of Che covers the facade of the Interior Ministry headquarters in Havana’s Revolution Plaza. It is a frequent backdrop to Fidel’s most important speeches, a virtual logo of the Cuban capital.

To this day Che remains a worldwide icon for radical change, his many political and economic blunders and guerrilla defeats mostly forgotten and largely overshadowed by his huge cultural impact. His romantic image, amplified by his early death and unorthodox communism, allowed his appeal to transcend ideological lines.

A 17-ton, five-story steel profile of Che covers the facade of the Interior Ministry headquarters in Havana’s Revolution Plaza. It is a frequent backdrop to Fidel’s most important speeches, a virtual logo of the Cuban capital.

“Che has become a universal, multigenerational symbol of the ’60s, like the Beatles, a man sufficiently political to capture the politics of the times in a broad sense without getting bogged down in the whole Cold War issue,” said Jorge Castaneda, a Mexican who authored one of three Che biographies published this year. But Che’s story is all about money, too. Cuba bought 10,000 Swiss-made Swatch watches carrying Che’s beret-clad and bearded visage and sold them in Havana boutiques. Former Culture Minister Armando Hart authored a multimedia CD-ROM on Che, priced at $60.

Havana music historian Santiago Felu has put together an anthology of 135 songs about Che, to go on sale in October. Felu said the songs will include traditional Cuban rhythms as well as rock and blues, and some whose lyrics are “critical of those who have misused and vulgarized Che’s image.”

Perhaps he means the Cuban street peddlers who offer tourists Che’s image on everything from wood carvings to hammered leather, and even dried sea grape leaves inscribed with some of his famous sayings.

It’s doubtful he means the key chains, posters and T-shirts with Che’s image always sold in Cuban government shops at $6 to $10 a pop.

Cuba drew the line on commercializing Che’s image last year, going after a British brewer that briefly manufactured a “Che” beer carrying his image and the captivating slogan, “Banned in the U.S. It must be good.”

Of course certain Che artifacts — the authentic ones, like rusty old rifles, rucksacks and yellowed photographs found in Bolivia and quietly brought back to Cuba by Cuban agents for years — cannot be mass produced. But they can still be exploited.

That applies especially to the ultimate Che artifact: his long-lost bones.

A Final Enigma

Even Gustavo Villoldo, who hunted Guevara all over the world, now acknowledges that these are probably Che’s remains. “Although I initially doubted it, all the evidence points to that,” he said after reviewing the evidence.

Yet another mystery remains, for the grave where the Cubans found seven remains does not match in significant details the grave where Villoldo says he buried Che and two other guerrillas.

“I cannot explain that at all,” he said. “That was the single most important moment in my life, and I can remember the details as though they are happening right now, right here. And they just don’t match.”

Villoldo heard of Che’s capture while he was in the Ranger’s advance command post in a nearby town. Villoldo rushed to Vallegrande, arriving on Oct. 9, just two hours before the helicopter with Che’s body landed at a dirt airstrip jammed with hundreds of journalists and curious townspeople.

“I never saw him alive, but I had no interest in that or in talking to him,” he said. “It was never personal to me, even though the fact that Che had contributed to my dad’s death was always in the back of my mind. It was just a job.”

The following day, Oct. 10, the top Bolivian military commanders and Villoldo gathered in the restaurant of Vallegrande’s lone hotel, the two-story Hotel Teresita, to discuss how to dispose of Che’s body, he recalled.

As in Che’s exhumation 30 years later, it was a race against the clock: The army officials had received word that some of Che’s relatives were on their way to Vallegrande to claim the body.

But both the Bolivians and Villoldo wanted to “disappear” it.

“We thought it was important to dispose of it in utmost security to deny Castro the bones and the possibility of building some sort of monument that he could exploit both ideologically and commercially,” recalled Villoldo.

Someone suggested cremating it, Villoldo said, but he argued that in the absence of a true crematorium in Vallegrande, “all we would be doing would be holding a barbecue. I told them that they had written a pretty page in the history of the Bolivian army, and that they should not end that way.”

Army commanders eventually settled on amputating the hands for future identification and then burying the body in secret. Army Chief Gen. Alfredo Ovando assigned Villoldo to carry out the decisions. Villoldo was photographed by Bolivian journalists looking over the shoulders of the two doctors who performed a quick autopsy of the corpse and later — after the journalists were gone — amputated its hands.

That’s when Villoldo clipped a lock of Che’s scraggly hair, at least initially for a U.S. Green Beret who had asked him for a keepsake. But, he ruefully acknowledged, he did keep a few strands.

“I don’t even recall if I cut it with a knife or scissors. I was not interested and I had no intention to keep it. I am not that kind of person. But in time, I figured, well . . .” He still has it, though he has never shown it in public.

Villoldo said he was provided with a security guard, a driver for a truck to transport the body and a second driver for the bulldozer that would bury it.

He took a nap, awoke at about 1:45 a.m., and went to the hospital laundry room. Che’s body was laid atop a laundry basin. On the dirt floor, a couple of feet away, were the rapidly decomposing corpses of two other rebels.

It’s the same scene described by helicopter pilot Nino de Guzman and by Alberto Suazo, who in 1967, as a young reporter for United Press International, saw Che’s corpse in the hospital. But Suazo recalled seeing “another three or four guerrilla corpses” laid out somewhere in the patio behind the hospital, which is consistent with Guzman’s account of flying in seven corpses.

Villoldo insists he saw only Che’s and two other bodies.

He ordered his helpers to load the three corpses on the truck. They drove to the airstrip in total darkness until he saw a likely spot near the walled Vallegrande cemetery, Villoldo recalled. He told the driver to stop.

The spot was south of the airstrip and west of the cemetery, in an area where a bulldozer had already been working nearby so that a fresh grave would not be apparent, Villoldo says.

But the mass grave dug up by the Cubans was north of the cemetery.

Villoldo says that while he sent one of his men to get the bulldozer, he took compass readings and paced off distances from four points that would allow him to find the exact spot again. He wrote nothing down, he says, but committed the measurements to memory.

Then they backed the truck to the edge of a natural in the ground and unloaded the three corpses. Villoldo ordered the bulldozer driver to cover them up.

Both Villoldo and the bulldozer driver, who still lives in Vallegrande and was interviewed by Inchaurregui, recall that it began to rain toward the end of the burial.

The bulldozer driver said he did not remember exactly how many bodies he buried or whether the site was north or west of the cemetery. He cannot even say for certain that Che was among the bodies, Inchaurregui told Tropic.

Inchaurregui said he believes Villoldo is lying or mistaken about burying only three bodies. “He obviously has political considerations for saying what he says. I am not surprised that after 30 years he would still be trying to lead everyone astray,” the Argentine said.

Villoldo’s CIA supervisor for the Bolivia mission, now retired in North Florida but still speaking only on condition of anonymity, said this: “Gus does not exaggerate. I would believe him if he says he buried three.”

So how about those seven remains? Who were ‘Willy’ Simon Cuba Sarabia who helped Che when he was wounded in the Quebrada de Yuro. Others were Orlando Tamayo “Antonio’; Aniceto Reynago Gordillo “Aniceto”; Rene Martinez Tamayo; Alberto Fernández Moises de Oca “Pacho” and Juan Pablo Chang Navarro.

Could the truck or bulldozer drivers have buried the other four guerrillas earlier in the day and then led an unwitting Villoldo to the same spot to bury Che and the two others?

“No way. I told them where to go, where to stop. I picked the spot all by myself,” Villoldo said.

Could the drivers have buried the other four bodies in the same spot as Che and the two others the next day, perhaps returning to where they had left the bulldozer after the rains came?

Not likely, said Inchaurregui. The pattern of digging marks in the pit from which the seven bodies were excavated indicated that a bulldozer had dug it with back-and-forth passes — not simply moved dirt atop bodies in a natural as Villoldo described.

Analysis of dirt hardness also showed the grave had one common floor of hard-packed dirt under all the bodies, and that all the seven bodies had been covered with the same dirt at the same time, Inchaurregui added.

“It looks to me like one opening and one closing of the grave. It’s seven bodies, not three. That’s the empirical evidence,” the anthropologist concluded.

Could Villoldo, by a zillion-to-one coincidence, have buried the three bodies in the same natural where some Bolivian army officer had earlier simply dumped four unburied corpses?

“I looked down into that and saw nothing,” said Villoldo. “I buried and covered three bodies. I know that for sure. I never saw seven bodies, I never even knew of seven bodies until much later.”

Today, a reduced team of Cubans working at a slower pace remains in Vallegrande, looking for some 23 more guerrilla corpses believed buried in unmarked graves around the region.

Still missing is the body of the second most notorious guerrilla: Tamara Bunker, a pretty, young Argentine of German descent code-named Tanya, a reputed KGB agent.

Villoldo remains determined to fly to Bolivia to visit the site where the handless remains were dug up and compare it to the compass bearings and distances he recorded the night he buried Che.

In the meantime, Villoldo tends his farm, pores over large scale maps of Vallegrande, re-reads his books on Che and tries to figure out how it’s possible to bury three bodies and dig up seven.

“Maybe you can headline this story Che: The End of the Myth,” he suggested.

But perhaps it is only the beginning of another.

Sources: Herald/Tamayo/Villoldo/TheCubanHistory.com

SEARCHING FOR “CHE” GUEVARA ‘DEAD OR ALIVE’ (III)

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

FIRST US INTERVENTION IN CUBA.

During the War in 1897, the Cuban Liberation Army maintained a privileged position in Camagüey and Oriente, where the Spanish only controlled a few cities. Spanish liberal leader Praxedes Sagasta admitted in May 1897: “After having sent 200,000 men and shed so much blood, we don’t own more land on the island than what our soldiers are stepping on”. The rebel force of 3,000 defeated the Spanish in various encounters, such as the battle of La Reforma and the surrender of Las Tunas on 30 August, and the Spaniards were kept on the defensive. Las Tunas had been guarded by over 1,000 well-armed and well-supplied men.

As stipulated at the Jimaguayú Assembly two years earlier, a second Constituent Assembly met in La Yaya, Camagüey, on 10 October 1897. The newly-adopted constitution decreed that a military command be subordinated to civilian rule. The government was confirmed, naming Bartolomé Masó as president and Dr. Domingo Méndez Capote vice as president.

Madrid decided to change its policy toward Cuba, replacing Weyler, drawing up a colonial constitution for Cuba and Puerto Rico, and installing a new government in Havana. But with half the country out of its control, and the other half in arms, the new government was powerless and rejected by the rebels.

The Maine incident

The Cuban struggle for independence had captured the American imagination for years and newspapers had been agitating for intervention with sensational stories of Spanish atrocities against the native Cuban population, intentionally sensationalized and exaggerated. Americans believed that Cuba’s battle with Spain resembled America’s Revolutionary War. This continued even after Spain replaced Weyler and changed its policies and American public opinion was very much in favour of intervening in favour of the Cubans.

In January 1898, a riot by Cuban Spanish loyalists against the new autonomous government broke out in Havana leading to the destruction of the printing presses of four local newspapers for publishing articles critical of Spanish Army atrocities. The US Consul-General cabled Washington with fears for the lives of Americans living in Havana. In response the battleship USS Maine was sent to Havana in the last week of January. On 15 February 1898 the Maine was rocked by an explosion, killing 268 of the crew and sinking the ship in the harbour. The cause of the explosion has not been clearly established to this day. In an attempt to appease the US the colonial government took two steps that had been demanded by President William McKinley: it ended the forced relocation and offered negotiations with the independence fighters. But the truce was rejected by the rebels.

The Spanish-American War – the Cuban theatre

The explosion of the Maine sparked a wave of indignation in the US. Newspaper owners such as William R. Hearst leapt to the conclusion that Spanish officials in Cuba were to blame, and they widely publicized the conspiracy although Spain could have had no interest in getting the US involved in the conflict. Yellow journalism fuelled American anger by publishing “atrocities” committed by Spain in Cuba. Hearst, when informed by Frederic Remington, whom he had hired to furnish illustrations for his newspaper, that conditions in Cuba were not bad enough to warrant hostilities, allegedly replied, “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.” McKinley, Speaker of the House Thomas Brackett Reed, and the business community opposed the growing public demand for war, which was lashed to fury by yellow journalism. The American cry of the hour became, Remember the Maine, To Hell with Spain!

The decisive event was probably the speech of Senator Redfield Proctor delivered on 17 March, analyzing the situation and concluding that war was the only answer. The business and religious communities switched sides, leaving McKinley and Reed almost alone in their opposition to the war. “Faced with a revved up, war-ready population, and all the editorial encouragement the two competitors could muster, the US jumped at the opportunity to get involved and showcase its new steam-powered Navy”. On 11 April McKinley asked Congress for authority to send American troops to Cuba for the purpose of ending the civil war there. On 19 April Congress passed joint resolutions (by a vote of 311 to 6 in the House and 42 to 35 in the Senate) supporting Cuban independence and disclaiming any intention to annex Cuba, demanding Spanish withdrawal, and authorizing the president to use as much military force as he thought necessary to help Cuban patriots gain independence from Spain. This was adopted by resolution of Congress and included from Senator Henry Teller the Teller Amendment, which passed unanimously, stipulating that “the island of Cuba is, and by right should be, free and independent”. The amendment disclaimed any intention on the part of the US to exercise jurisdiction or control over Cuba for other than pacification reasons, and confirmed that the armed forces would be removed once the war is over. Senate and Congress passed the amendment on 19 April, McKinley signed the joint resolution on 20 April and the ultimatum was forwarded to Spain. War was declared on 20/21 April 1898.

“It’s been suggested that a major reason for the US war against Spain was the fierce competition emerging between Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World and William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal.” Joseph E. Wisan wrote in an essay titled “The Cuban Crisis As Reflected In The New York Press”, published in “American Imperialism” in 1898: “In the opinion of the writer, the Spanish-American War would not have occurred had not the appearance of Hearst in New York journalism precipitated a bitter battle for newspaper circulation.” It has also been argued that the main reason the U.S. entered the war was the failed secret attempt, in 1896, to purchase Cuba from a weaker, war-depleted Spain.

Propaganda of the Spanish American War

Hostilities started hours after the declaration of war when a US contingent under Admiral William T. Sampson blockaded several Cuban ports. The Americans decided to invade Cuba and to start in Oriente where the Cubans had almost absolute control and were able to co-operate, for example, by establishing a beachhead and protecting the US landing in Daiquiri. The first US objective was to capture the city of Santiago de Cuba in order to destroy Linares’ army and Cervera’s fleet. To reach Santiago they had to pass through concentrated Spanish defences in the San Juan Hills and a small town in El Caney. Between 22 and 24 June the Americans landed under General William R. Shafter at Daiquirí and Siboney, east of Santiago, and established a base. The port of Santiago became the main target of naval operations. The US fleet attacking Santiago needed shelter from the summer hurricane season. Thus nearby Guantánamo Bay with its excellent harbour was chosen for this purpose and attacked on 6 June (1898 invasion of Guantánamo Bay). The Battle of Santiago de Cuba, on 3 July 1898, was the largest naval engagement during the Spanish-American War resulting in the destruction of the Spanish Caribbean Squadron (Flota de Ultramar).

Resistance in Santiago consolidated around Fort Canosa, all the while major battles between Spaniards and Americans took place at Las Guasimas (Battle of Las Guasimas) on 24 June El Caney Battle of El Caney and San Juan Hill Battle of San Juan Hill on 1 July 1898 outside of Santiago [48] after which the American advance ground to a halt. Spanish troops successfully defended Fort Canosa, allowing them to stabilize their line and bar the entry to Santiago. The Americans and Cubans forcibly began a bloody, strangling siege of the city which eventually surrendered on 16 July after the defeat of the Spanish Caribbean Squadron. Thus, Oriente was under control of Americans and the Cubans, but US General Nelson A. Miles would not allow Cuban troops to enter Santiago, claiming that he wanted to prevent clashes between Cubans and Spaniards. Thus, Cuban General Calixto Carcía, head of the mambi forces in the Eastern department, ordered his troops to hold their respective areas and resigned, writing a letter of protest to General Shafter.

http://youtu.be/st-6qgsmEZ0

After losing the Philippines and Puerto Rico, which had also been invaded by the US, and with no hope of holding on to Cuba, Spain sued for peace on 17 July 1898. On 12 August the US and Spain signed a protocol of Peace in which Spain agreed to relinquish all claim of sovereignty over and title of Cuba. On 10 December 1898 the US and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris, recognizing Cuban independence Although the Cubans had participated in the liberation efforts, the US prevented Cuba from participating in the Paris peace talks and signing the treaty. The treaty set no time limit for US occupation and the Isle of Pines was excluded from Cuba. Although the treaty officially granted Cuba’s independence, US General William R. Shafter refused to allow Cuban General Calixto García and his rebel forces to participate in the surrender ceremonies in Santiago de Cuba.

The first US occupation and the Platt amendment

After the Spanish troops left the island in December 1898, the government of Cuba was handed over to the United States on 1 January 1899. The first governor was General John R. Brooke. Unlike Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, the United States did not annex Cuba because of the restrictions imposed in the Teller Amendment. The US administration was undecided on Cuba’s future status. Once it had been pried away from the Spaniards it was to be assured that it moved and remained in the US sphere. How this was to be achieved was a matter of intense discussion and annexation was an option, not only on the mainland but also in Cuba. McKinley spoke about the links that should exist between the two nations.

Brooke set up a civilian government, placed US governors in seven newly created departments, and named civilian governors for the provinces as well as mayors and representatives for the municipalities. Many Spanish colonial government officials were kept in their posts. The population were ordered to disarm and, ignoring the Mambi Army, Brooke created the Rural Guard and municipal police corps at the service of the occupation forces. Cuba’s judicial powers and courts remained legally based on the codes of the Spanish government. Tomás Estrada Palma, Martí’s successor as delegate of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, dissolved the party a few days after the signing of the Paris Treaty in December 1898, claiming that the objectives of the party had been met. The revolutionary Assembly of Representatives was also dissolved. Thus, the three representative institutions of the national liberation movement disappeared.

Before the US officially took over the government, it had already begun cutting tariffs on US goods entering Cuba without granting the same rights to Cuban goods going to the US. Government payments had to be made in US dollars. In spite of the Foraker Amendment, prohibiting the US occupation government from granting privileges and concessions to US investors, the Cuban economy, facilitated by the occupation government, was soon dominated by US capital. The growth of US sugar estates was so quick that in 1905 nearly 10% of Cuba’s total land area belonged to US citizens. By 1902 US companies controlled 80% of Cuba’s ore exports and owned most of the sugar and cigarette factories.

The US Army also began a massive public health program to fight endemic diseases, mainly yellow fever, and an education system was organized at all levels, increasing the number of primary schools fourfold.

Elections and independence

Voices soon began to be heard, demanding a Constituent Assembly. In December 1899 the US War Secretary assured that the occupation was temporary, that municipal elections would be held, that a Constituent Assembly would be set up, followed by general elections and that sovereignty would be handed to Cubans. Brooke was replaced by General Leonard Wood to oversee the transition. Parties were created, including the Cuban National Party, the Federal Republican Party of Las Villas, the Republican Party of Havana and the Democratic Union Party. The first elections for mayors, treasurers and attorneys of the country’s 110 municipalities for a one-year-term took place on 16 June 1900 but balloting was limited to literate Cubans older than 21 and with properties worth more than 250 US dollars. Only members of the dissolved Liberation Army were exempt from these conditions. Thus, the number of about 418,000 male citizens over 21 was reduced to about 151,000. 360,000 women were totally excluded. The same elections were held one year later, again for a one-year-term.

Elections for 31 delegates to a Constituent Assembly were held on 15 September 1900 with the same balloting restrictions. In all three elections, pro-independence candidates, including a large number of mambi delegates, won overwhelming majorities.[60] The Constitution was drawn up from November 1900 to February 1901 and then passed by the Assembly. It established a republican form of government, proclaimed internationally-recognized individual rights and liberties, freedom of religion, separation between church and state, and described the composition, structure and functions of state powers.

On 2 March 1901, the US Congress passed the Army Appropriations Act, stipulating the conditions for the withdrawal of United States troops remaining in Cuba following the Spanish-American War. As a rider, this act included the Platt Amendment, which defined the terms of Cuban-US relations until 1934. It replaced the earlier Teller Amendment. The amendment provided for a number of rules heavily infringing on Cuba’s sovereignty:

Cuba would not transfer Cuban land to any power other than the United States.

Cuba would contract no foreign debt without guarantees that the interest could be served from ordinary revenues.

The right to US intervention in Cuban affairs and military occupation when the US authorities considered that the life, properties and rights of US citizens were in danger.

Cuba was prohibited from negotiating treaties with any country other than the United States “which will impair or to impair the independence of Cuba”.

Cuba was prohibited to “permit any foreign power or powers to obtain … lodgement in or control over any portion” of Cuba.

The Isle of Pines (now called Isla de la Juventud) was deemed outside the boundaries of Cuba until the title to it was adjusted in a future treaty.

The sale or lease to the United States of “lands necessary for coaling or naval stations at certain specified points to be agreed upon.” The amendment ceded to the United States the naval base in Cuba (Guantánamo Bay) and granted the right to use a number of other naval bases as coal stations.

As a precondition to Cuba’s independence, the US demanded that this amendment be approved fully and without changes by the Constituent Assembly as an appendix to the new constitution. Faced with this alternative, the appendix was approved, after heated debate, by a margin of 4 votes. Governor Wood admitted: “Little or no independence had been left to Cuba with the Platt Amendment and the only thing appropriate was to seek annexation”.

In the presidential elections of 31 December 1901, Tomás Estrada Palma, a US citizen still living in the United States, was the only candidate. His adversary, General Bartolomé Masó, withdrew his candidacy in protest against US favoritism and the manipulation of the political machine by Palma’s followers. Palma was elected to be the Republic’s first President, although he only returned to Cuba four months after the election. The US occupation officially ended when Palma took office on 20 May 1902.

Cuba in the early 20th century

In 1902, the United States handed over control to a Cuban government that as a condition of the transfer had included in its constitution provisions implementing the requirements of the Platt Amendment, which among other things gave the United States the right to intervene militarily in Cuba. Havana and Varadero became popular tourist resorts. The Cuban population gradually enacted civil rights anti-discrimination legislation that ordered minimum employment quotas for Cubans.

President Tomás Estrada Palma was elected in 1902, and Cuba was declared independent, though Guantanamo Bay was leased to the United States as part of the Platt Amendment. The status of the Isle of Pines as Cuban territory was left undefined until 1925 when the United States finally recognized Cuban sovereignty over the island. Estrada Palma, a frugal man, governed successfully for his four year term; yet when he tried to extend his time in office, a revolt ensued. In 1906, the United States representative William Howard Taft, notably with the personal diplomacy of Frederick Funston, negotiated an end of the successful revolt led by able young general Enrique Loynaz del Castillo, who had served under Antonio Maceo in the final war of independence. Estrada Palma resigned. The United States Governor Charles Magoon assumed temporary control until 1909.

Source: Wiki/ USHispWAR/InternetPhotos/YouTube/TheCubanHistory.com

FIRST US INTERVENTION IN CUBA.

The Cuban History, Arnoldo Varona, Editor

FIRST HAND ACCOUNT OF BAY OF PIGS INVASION (US RECORDS)

BOP INVASION

FIRST HAND ACCOUNT

MAY 1961

[Reference: Dade County OCB file #153-D]

CI 153-D

DATE: May 29, 1961

TO: THOMAS J. KELLY, Metropolitan Sheriff

FROM: LT. FRANK KAPPEL, Supervisor, Criminal Intelligence

SUBJECT: CUBAN COUNTER-REVOLUTIONARY ACTIVITIES –

Additional Information – ULISES CARBO

Reference is made to the report under the same case number dated May 21, 1961 in which the initial contact with the delegation of ten Cuban prisoners was related. The prisoners arrived in Miami on May 20, 1961 to negotiate an offer made by FIDEL CASTRO to exchange the captured invaders of Bahia de Cochinos for 500 tractors.

The leader of the group, ULISES CARBO, a personal acquaintance of the writer, related several episodes of the invasion in addition to information concerning the treatment of the captives by the Communist regime of Cuba.

ULISES CARBO was aboard the transport “Houston” when the invasion force sailed from Puerto Cabezas toward the Bahia de Cochinos landing beaches. Just prior to departure, the ranking officers aboard the transport had a strong argument with a C.I.A. agent known as “Jerry” about the feasibility and need for anti aircraft protection. As a result, eight .50 caliber machine guns were installed on the “Houston”. The “Houston” was the slowest vessel in the convoy, her speed being only eight knots. This caused an earlier departure from Puerto Cabezas and by consequence a longer stay at sea.

The “Houston” was carried two battalions plus fuel and ammunition. The troops were supposed to be transferred to waiting L.C.I.’s which, in turn, would land them to the selected beach.

When the transport reached the rendezvous point at the inner tip of the Bay of Cochinos, the L.C.I.’s failed to materialize and consequently t he troops had to be landed by outboard launches which were to be used only for beach patrol duty.

At approximately 2 a.m. when the “Houston” approached the objective, it became necessary to lower the patrol launches and lifeboats to land the troops. In contrast with orders of strict silence to be observed by the troops, the lowering of the boats was a noisy operation. It is the opinion of CARBO that the militiamen ashore were alerted by the noise of the steam operated davits when they put the small boats overboard. CARBO related an incident of a man who dropped a clip on deck and was immediately placed under arrest while almost immediately afterwards, the noisy davits were put in operation.

As a consequence of the lack of appropriate landing means, the disembarking of the personnel, which was originally planned to take only one and one and a half hours, took such a long time to accomplish, that at daylight only half of the personnel had reached shore.

With daylight the “Houston” came under constant attack by enemy aircraft. As a consequence all landing operations had to be halted after an attempt to land a party of eight men ended with the death of five as the strafing aircraft singled the small craft for target.

The “Houston” was escorted by the “Barbara J” which, according to CARBO, had four United States officers aboard. These officers were observed manning the anti aircraft guns of the vessel and drew the admiration of the Cubans for their courage.

At approximately 8:00 a.m., a Seafury launched two rockets against the “Houston” that completely disabled the transport which had already suffered damages in the ruder during a previous attack. Since there was no possibility of repairing the two large holes amidships produced by the rockets, Captain LUIS MORSE DELGADO decided to proceed toward land and beach the ship.